Yale-NUS alumnus explores natural and urban Singapore through poetry

Shawn Hoo (Class of 2020) shares his journey crafting his debut poetry chapbook and his career at New York University Shanghai.

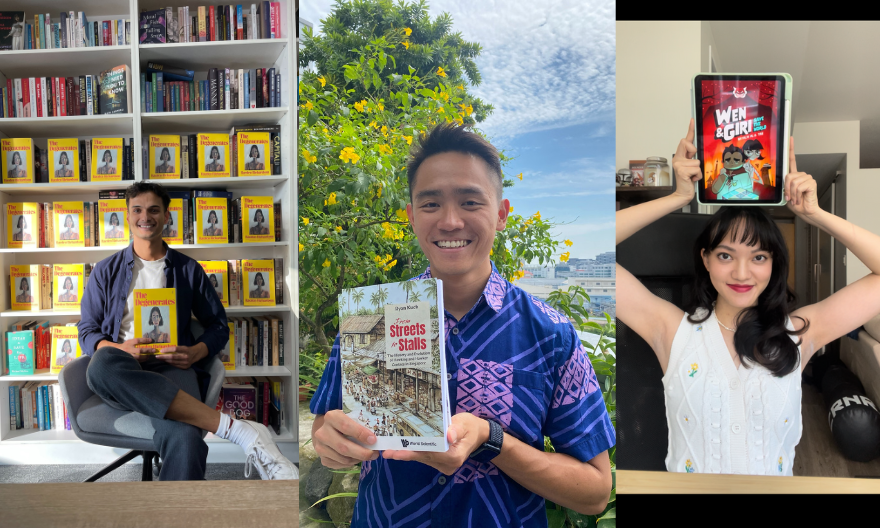

Alumnus Shawn Hoo (Class of 2020). Image provided by Victoria Oliha.

Thoughtful and empathetic, Yale-NUS College students are no strangers to channelling their creative energies towards discussing different topics, including the natural environment. After graduating with a major in Literature, alumnus Shawn Hoo (Class of 2020) recently released his debut poetry chapbook, Of the Florids, winner of the 2021 Diode Editions Chapbook Prize.

The cover of Shawn’s upcoming poetry chapbook. Image provided by Diode Editions.

Shawn currently works as a Global Writing and Speaking Fellow at New York University (NYU) Shanghai. He conceptualised and wrote most of his chapbook during the Advanced Poetry Writing class taught by Lawrence Lacambra Ypil, Senior Lecturer in Humanities (Creative Writing) at Yale-NUS College. The chapbook explores the intricate connections between natural and urban worlds. Shawn shared some of his motivations for and experiences with writing the chapbook.

What was your inspiration behind Of the Florids?

I was first inspired by a line from Mary Oliver’s The Poetry Handbook: “The language of poetic diction is romantic and its images come from the natural world”. I first read this in a class with Lawrence Ypil, and wondered to myself: but do my images really come from the natural world? What does this seemingly universal statement mean for someone who’s grown up in a city all his life? Of the Florids contains tapirs but also turnstiles, cicadas, and colonial naturalists. The chapbook started as an investigation into the sources of my own metaphors, and found its way through natural histories, myths, languages, and other routes.

How did the chapbook evolve over the process of writing it?

The soundscape and textures of the chapbook evolved over time. Something that I listen for in a book of poems is its musical texture, and polyphony is one of my favourite textures. I wrote poems in different kinds of registers according to what I felt was missing and placed longer poems beside shorter ones. The cover design, which I love, and the interior images – which were my publisher’s idea – all came later. I always made sure that these interior images provided a visual counterpoint and their own narratives or poetics with their own music.

How do you hope readers will react to Of the Florids?

With enchantment. The miniature of a chapbook allows for immersion, but I am striving for an expansive world as well. I hope that it will allow readers to look at their relationship to the natural world with new language. I’m also hoping that non-poets will give poetry a chance.

What were some challenges you faced in crafting the chapbook? What did you discover through writing it?

Prior to writing Of the Florids, I had been writing poems for perhaps ten years, but did not think of them as a collective. It’s been satisfying working at the architectural level of the book, and it’s been as exciting to approach other poets’ books as books. There is a whole social process behind the making of a book – the writing, of course, but also editing, designing, publicising, reviewing, selling, even interviews like this – that isn’t immediately obvious if you haven’t been involved in a book’s life stages. I’m the kind of person to be fascinated by the becoming of a book so I’ve also started an irregular newsletter titled The Making of the Florids. It provides a little glimpse into the labour that goes into the book in your hands.

Can you share any behind-the-scenes moments of the chapbook?

I spent much time looking at books and archives, which is a pleasure in itself apart from the act of writing. For example, it was fascinating to look at natural history illustrations that mostly came out of various colonial encounters: from the drawings of Raffles and Farquhar (by which I mean they were mostly outsourced to other artists), to those by the French natural historians Diard and Duvaucel, to even illustrations by the Japanese during the second world war. Faris Joraimi (Class of 2021) writes beautifully about the aesthetics and labour behind a folio of drawings that predated 1819 in “A Banquet of Malayan Fruits”. In any case, all these demonstrate how drawing was such a crucial tool to imperial knowledge and activity.

How did your education at Yale-NUS shape your identity as a writer? How did it inform the creation of Of the Florids?

For most of my time at Yale-NUS, I found it quite difficult to reconcile the kinds of academic-scholarly writing expected of me and my poetic impulses. The two modes of writing seemed hostile to each other and I felt like I had to choose. More recently, I have started to see my own writing as traversing between critical and creative worlds; Of the Florids is a modest foray into what that might look like. I have all my professors to thank, but especially Lawrence Ypil, Carissa Foo, and Ma Shaoling for showing me how to, whenever possible, be both. In fact, I wrote most of the book in Larry’s class!

Yale-NUS was a time of deep conversation, with such intensity and generosity that was its own, difficult to repeat.

Are there any upcoming projects that you’re working on?

I spent my time as a Writing and Speaking Fellow at NYU Shanghai, writing a series of meandering fragments on queer Sinophone cinema – films such as Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine, Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together and Tsai Ming-liang’s Rebels of a Neon God. I’ve also recently been researching the histories and currencies of the Hokkien language in Singapore and the region, thinking about the status of non-Mandarin Chinese languages, and speculating about their futures.

Hopefully, I’ll get to do interesting things with Of the Florids beyond the page! More immediately, I’ll be running a workshop titled The Archive as Poetic Material with Sing Lit Station on 23 July 2022 and reading from Of the Florids with the poets Daryl Lim and Mok Zining later that evening.

How has your career at NYU Shanghai been thus far? What have you learned while working there?

The need to think more consciously about multilingualism and translation. Most, if not all, students at NYU Shanghai graduate with proficiencies in English and Mandarin; many others grew up in even more multilingual environments. If we begin from the assumption that multilingualism and translation are the norm, then it seems to me that it will have deep implications for how we choose to write, read, talk, teach and live.

How did your time at Yale-NUS prepare you for working at NYU Shanghai?

The forms of writing I was encouraged to do and read at Yale-NUS gave me a broad repertoire of vocabularies to talk to my students and colleagues at NYU Shanghai about what writing can achieve. We need more interesting, idiosyncratic ways of talking about writing!