Past Grant Recipients (AY 2022/2023)

Ben Andrew Olsen| Assistant Professor of Science (Physics)

Project

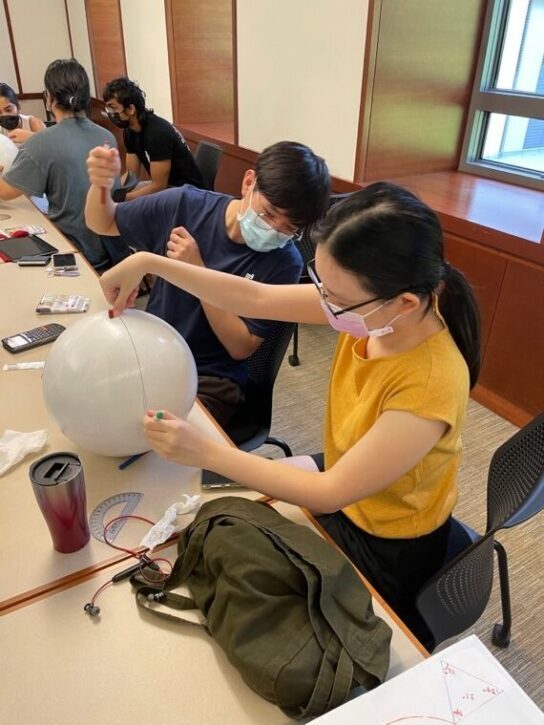

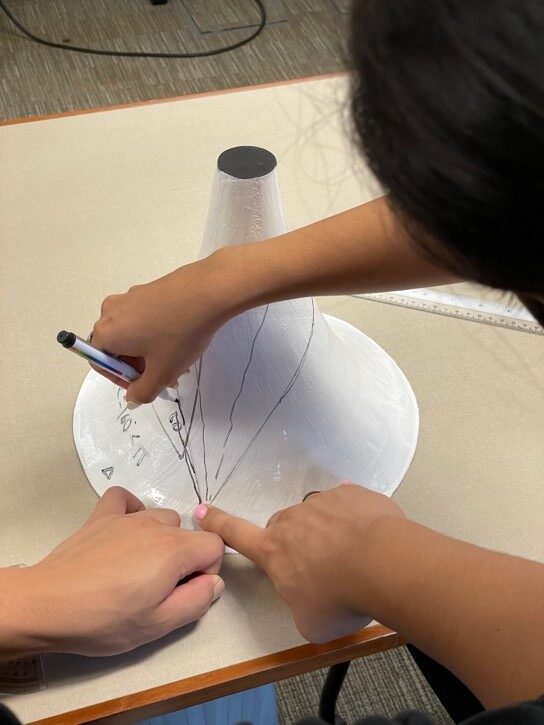

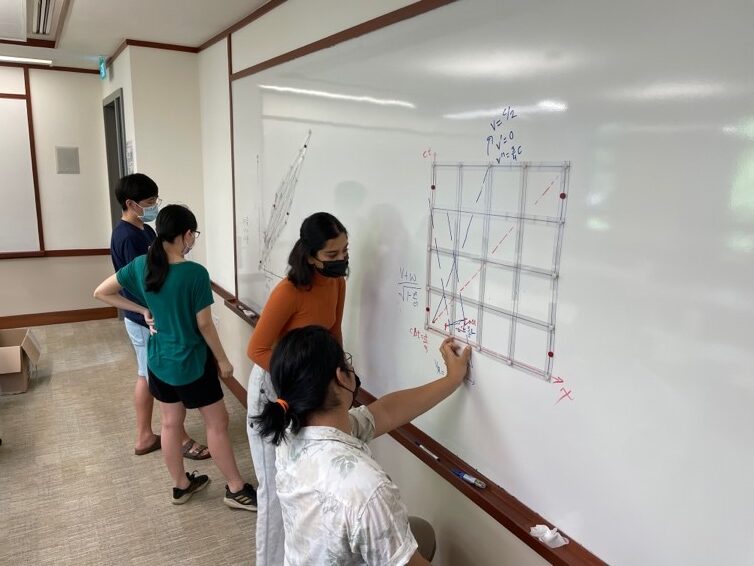

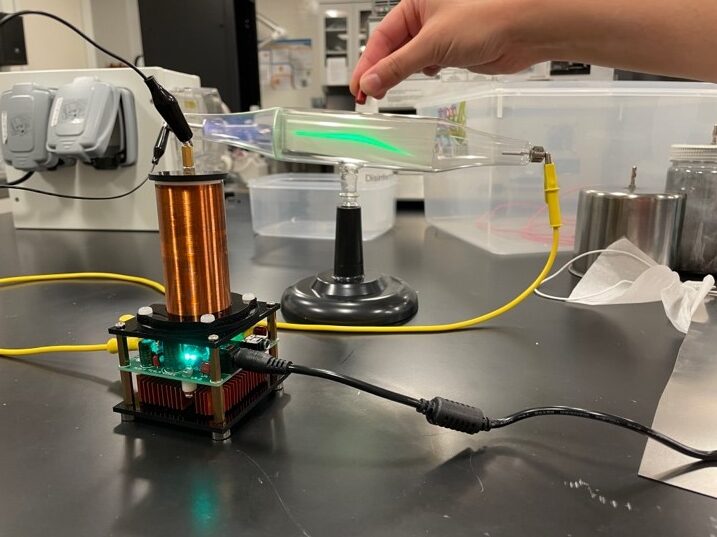

My goal with the TEG was to explore some ways to make teaching advanced physics topics less abstract and more intuitive. For many topics, students can draw on their daily experience to reason about the physics, such as the experience of wearing glasses when studying optics, or weight lifting when studying pulleys. However, for many advanced topics in Introduction to Electrodynamics and Physics of Curved Spacetime, students’ lived experience has little connection to magnetic field lines or relativistic motion. I aimed to develop experiential learning aids (ELAs) that helped make some abstract topics in these courses more visible and tangible, to let students build their own physical intuition.

For electrodynamics, physics educators have developed several ELAs (which are often used at other institutions as lecture demonstrations) that help students visualize electric and magnetic fields. These begin with either a van de Graaff generator or a Tesla coil, and employ a range of materials that respond to electromagnetic fields (like foam beads covered in graphite, or nylon rods, or low-pressure cathode ray tubes). With the TEG, I purchased the components to assemble these systems, and developed in-class inquiry-based activities for students to explore.

In Curved spacetime, where ELAs are less well-developed, I tried some untested new ideas. First, I created flexible coordinate axes out of clear polycarbonate that distort to show the operation of a Lorentz transformation (describing how physics looks from two different frames of reference), and attach to the whiteboards in classrooms. Second, I created curved whiteboards for the students to draw on – spheres, pseudospheres, toroids, and Schwartzschild geometry. I created computer models of the shapes, then used the CNC mill in the Fabrication Studio to cut them from polystyrene foam, cover them with magnetic paint, and a whiteboard top surface.

Outcomes

In Electromagnetism, the ELAs were successful, as expected based on experiences at other institutions. One course review read: “The learning aids were fun, I think it’s good to have a physical system to test out predictions from the text, especially for E&M fields in materials.”, and another student wished there were more ELAs for other topics.

In Curved Spacetime, the deformable coordinate systems, while helping students reason about directions correctly, led to more misconceptions about lengths in other coordinate systems. I haven’t come up with a good solution to this issue yet. For the curved whiteboards, one student wrote: “really helped with visualisation and made unfamiliar concepts tangible. Maybe more exercises with them.”. Based on assignments and exams, this cohort of students performed approximately as well as past cohorts, and the students were much more engaged during class. In the future, I would like to make enough whiteboards so each pair of students could work together with one of each shape simultaneously, since groups of two seemed to maximize student engagement.

Overall, I think the ELAs improved engagement in both courses enough where I will continue to develop them in future course offerings.

Bilin Zhuang| Assistant Professor of Science (Chemistry)

Project

With the Teaching Engagement Grant, I have been able to bring all 36 students of YSC 1223 Science of Everyday Cooking to Brettschneider’s Baking and Cooking School to attend a one-day bread-baking workshop. In YSC 1223 Science of Everyday Cooking, students learned about food molecules and how they are responsible for the texture and flavour of the food. In class, the students also performed experiments focusing on particular topics, for example, investigating the phase transformation of chocolate and observing the structure of mayonnaise under the microscope. Bread baking involves a complex array of science taught in the course. The bread-baking workshop, led by Master chefs Dean Brettschneider and Jenna White, brings together all the science topics covered in YSC 1223 in the process of bread baking.

Outcomes

The workshop was a great experiential-learning activity for the course, and the students gave enthusiastic feedback for this experience! The chefs are very renowned and knowledgeable. They explained the concepts behind dough development, gluten formation, and the baking process in a very in–depth manner. The students got to solidify the concepts about macromolecules they learned in class and see how professional chefs used these concepts. Additionally, they learned new techniques in baking, which is a valuable life skill! Each student baked three big loaves of bread at the workshop (a focaccia, a white loaf, and a fougasse) and brought them back to the residential colleges to share with their friends. One student commented that the workshop “was a comprehensive experience that was both fun and educational.” The other said, ” I cannot stress how wonderful the bread-making workshop is. Within that one workshop, I learned so much scientific knowledge and how to make bread properly. I am very excited to use these skills that I have learned beyond this course.”

Past Grant Recipients (AY 2021/2022)

Eduardo Lage-Otero | Senior Lecturer of Humanities (Spanish)

Project

Learning a new language is an important goal for many university students. Although individual motivations will vary, many students embark on this process each semester at Yale-NUS and at NUS. Enrolling in a language course may be their first step, but reaching an advanced level of proficiency demands more time and effort than what a course may require of them. Well-designed language courses provide a guided path towards building confidence and developing the language skills needed to function in various settings. At the same time, language students frequently supplement formal instruction with other co-curricular activities and experiences that take them beyond their comfort zone and help them manage increasingly complex tasks and situations. One of the main goals of the Language Portfolio project is to make the links between these in-class and out-of-class activities more explicit (Chaudhuri & Cabau, 2017; Pérez Cavana, 2012).

Prior to Academic Year (AY) 2020/21, there was no easy way at Yale-NUS to help students monitor, self-regulate, and reflect on how their language learning journey progressed over time. There was a need to provide them with a tool to connect a variety of activities with individual learning goals, bring together seemingly unrelated experiences into a coherent whole, and map them onto an international language standard, such as the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR)1. An easy-to-use and versatile platform was needed to help language learners gain a deeper understanding of the language learning process while reflecting upon how they engage with the new language in different contexts and at different levels. In a more practical way, we wanted them to easily showcase their language achievements and plurilingual identity to others (Goullier, 2010), not just at the college but also to prospective employers.

Outcomes

Thanks to a Teaching Enhancement Grant2 (TEG), we reviewed the literature on best practices in language portfolio use, prototyped various solutions, and analysed what may work best in our context. After considering several options, we decided to adapt the European Language Portfolio Project (Schneider & Lenz, 2001; Wernicke & Sabatier, 2017) and integrate it into our College’s learning management system (LMS), Canvas. The advantage of using Canvas was that our students are already familiar with it, and it has built-in functionality that works well with the stated goals of the language portfolio.

During Semester 2, AY20/21, we ran a small pilot with two introductory language courses to assess students’ perceptions of the language portfolio and its impact on self-regulated learning and language learning strategies. In follow-up interviews with the study participants, a student noted how “the questions are having me look back and reflect upon how I was approaching language and also, it offers a lot of solutions, or like good learning strategies”. Several students also appreciated setting short- and long-term goals, although one expressed frustration with the latter, noting: “I didn’t find the long-term goals to be as helpful, in my opinion, because when you set them in the beginning, you don’t really know what’s going to happen through the course of the semester”. This highlighted the need for more guidance from instructors on how to work with different components of the portfolio throughout the semester. A psychology student, in turn, indicated how “the questions […] get you to reflect upon how you were learning the language. It’s like, in psychology, there’s this word called metacognition. That’s how I felt”. Another student valued the can-do checklists for each language level, remarking how “it usually feels very vague to be [doing] one level of Spanish […] So, I found those checklists helpful to be able to evaluate where I was in my language learning process”.

Students also recommended ways of making the portfolio platform more engaging and user-friendly. Some commented that it was text-heavy, at times making it difficult to understand. Others noted that more explicit guidance could be given on what they should focus on over time. Some suggested gamifying the platform and increasing the level of interactivity. As a result of this pilot phase, we are reviewing the feedback received and considering ways that will add value to the students’ language portfolio and lead to students’ greater engagement with it over time. This project also has implications for how language educators assess students in the language classroom, and how we integrate the Language Portfolio into other areas of their college experience. These are some of the ways in which we have begun to integrate this resource:

- Asking students to submit a PDF of their language passport at the end of a language course with their self-assessment of where their language proficiency improved (see Figure 2 for self-assessment grid);

- Developing level-appropriate course assignments students can easily add to their language dossier. These include short videos, sample newspaper articles, essays, and recorded presentations;

- Including the language passport as part of the application process for various campus positions;

- Integrating the language portfolio into immersive summer language opportunities and study abroad programmes.

We are excited about the possibilities the language portfolio offers our language students to become more strategic and reflective learners while making language instructors consider other forms of assessing their students’ performance.

Emily Dalton| Lecturer of Humanities (Literature)

Project

This Teaching Engagement Grant helped facilitate the development of an online learning portal designed to support the teaching of medieval literature at the College. Encountering medieval European literature for the first time can be a challenging and sometimes alienating experience, and the project aimed to assemble a set of resources on language, literary history, manuscripts, and visual culture that would enable students to approach texts in more historically sophisticated ways. The learning portal was also collaborative: students in each of my electives were invited to contribute to the site by curating a compendium of key terms and concepts for medieval literary studies and by sharing their analytical and creative works inspired by our texts.

Outcomes

The site was launched in the fall of 2021, and now charts the past three years of students’ journeys through the world of medieval literature. I have drawn on the site to complement my own teaching, both in medieval electives and in Literature and Humanities, in which students reading Marie de France’s twelfth-century Lais were invited to explore the cultural context and thematic concerns of the text through short articles on the site. Last spring, students in Medieval Romance: Magic and the Supernatural collaborated on a compendium of self-selected keywords for the study of romance, expanding their critical vocabulary and enriching our discussions of the literary imagination and textual cultures of medieval Europe.

In addition, the project has given students the opportunity to share their creative engagements with medieval texts with the wider community. Bringing together original musical compositions, visual artwork, dance choreography, animation, theatre, and other art forms, the site reflects the range and depth of students’ imaginative responses to these texts: one student, for example, created a spherical model with the short Middle English poem “Earth” printed in many languages in order to evoke the poem’s interest in the collapse of distinctions between material and matter and the erosion of linguistic meaning in the face of death. Another student examined intersections between the lost sense of communion with the dead in the wake of theological change in early modern England, and the state-sanctioned displacement of physical memorials like Bukit Brown in contemporary Singapore. Such imaginative and interdisciplinary engagements serve as a valuable reminder of the continued capacity for pre-modern texts to speak to us across the centuries and of the rich possibilities of medieval studies within a liberal arts environment, helping to give students a sense of belonging within a larger community of readers.

Philip Johns | Senior Lecturer of Science (Life Sciences)

Project

Integrated tools for citizen science, community engagement, and pedagogy

Citizen or community science is a way of crowdsourcing data collection, and it has often been touted as a way of engaging communities in science. My students and I have been working with local communities, as well as “gleaning” data from public sources, for years. Doing this has allowed us to answer questions that would have been impossible to address otherwise – including on otter social behaviour and cat cognition. Community science is often applied to questions of ecology, and especially to the occurrence of biodiversity. However, my students work with communities to address questions of animal behaviour.

Several community science platforms exist, the most popular being iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org). However to the best of my knowledge none store and share video. Several social media platforms that accept video exist, but they do not necessarily share the information that community scientists need, e.g., to find animals.

My goal in this grant was to:

- Create a citizen science tool that allowed citizen science projects to easily compile and share citizen science data related to animal behaviour;

- Create a survey that allowed us to measure the impact of participating in citizen science projects, as well as taking certain modules, on participant awareness of Singapore’s biodiversity.

We had planned to create an online platform to advertise and share community science projects run by Yale-NUS. However, with the announcement in August we focused on these two goals.

Outcomes

We created a set of loosely integrated tools that allow community scientists to “scrape” videos off of Instagram (https://www.instagram.com ), if they have certain hashtags (#). This allows coordinators of citizen science projects to amass videos from participants as long as they include the appropriate hashtag. Notably, because most people already use Instagram or related platforms (Facebok), this doesn’t require a new app. Instagram includes information about where videos were collected. The tool we created also allows participants to record other hashtags, and we think this will allow the growth of “folksonomies” within community science studies, which should help aid engagement. The tool is currently available on GitHub (https://github.com/mjerricho/citizen-science-IG.git ), I am presenting it at the IUCN Otter Congress in September, in a session devoted to community engagement. We will write a manuscript presenting this tool.

We also created a survey for student participants in certain modules (e.g, Conservation Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, Animal Behaviour), as well as participants in citizen and community science research. The goal is to assess people’s awareness of Singapore’s biodiversity, both by asking directed questions about attitude, as well as quizzing participants on common animals in Singapore. We have before- and after-surveys for module participants, to see how much their awareness has changed (if at all), with the understanding that students are likely to self-select for certain kinds of modules. We plan to also use this survey in community-oriented studies of animal behaviour.

Past Grant Recipients (AY 2020/2021)

Andrew Hui | Associate Professor of Humanities (Literature)

Project

With a grant from CTL, I was able to edit the second volume of The Dante Journal of Singapore, written and produced by the students of Yale-NUS College. The College was founded in 2011 and began operations in 2013, we graduated our first class in 2017, and the first volume of the journal was published that year. There is a saying here that if you do something once it is groundbreaking, and if you do something twice it becomes a tradition.

This volume was edited in the wake of COVID-19, economic, racial, and social upheaval. Yet these essays were written two years ago; it is just the feature of academic publishing that we work at an intergalactic speed. What we read, most of the time, are the radiance of stars visible only many years later due to the velocity of their light.

The essays as such represent the students’ travelogue, by now a two-year journey. Whereas most final papers in class are quickly written and then summarily hidden away, we worked on them, refined them, and made them exponentially better. The goal of this publication is to build an “authentic learning experience,” in the current buzzword of pedagogy. The contributors learn the process of journal submission, revision, and peer review; the student editors learn the process of running a journal. These are essential skills not only for the students who wish to go on to graduate school, but also for any professional field.

Outcomes

Now, thanks to a grant from the College’s Teaching and Learning Centre, we are able to make this again into an online and print journal. Thus I am honored and delighted to present to the reader these works—all pieces of undergraduate research that make a real contribution to the 700-year old tradition of Dante scholarship.

Nicholas Lua’s paper begins with an apt cross-cultural comparison to the classical tradition of Chinese literature to think about poetic friendship across generations. Lua then gives a beautiful reading of Statius’ recognition scene with Virgil in Purgatorio 21, and teases out all the haunting powers of failure, redemption, and sweet sadness imbedded in the verses.

For Kevin Wong, his question is the meaning of antico, and he carefully catalogues its fifty occurrences. Through this lexical aperture, Wong is able to expand his scope to think about not only Dante’s engagement with Christian and pagan antiquity, but also how Dante propels himself into the future by envisioning himself as a proleptic antico.

With philological precision and theological scope, Kan Ren Jie explores the decisive role Psalm 50, miserere mei, plays in the narrative arc of the Commedia. Occurring in Inf. 1, Purg. 5 and Para. 32, Kan argues that “Through his evocation of this Psalm, Dante dramatizes the pilgrim’s conviction of sin and utter abjection, leading to intensified and sanctified desires and actions through purgation, while displaying real, impending hope of attaining perfection and union with God.”

In “Tale of Two Cities,” Brandon Lim convincingly demonstrates that in Purgatorio 13-14, “Dante defines envy not only as a moral and spiritual deficiency in character, but rather, he treats it historically: envy, a passion gone awry, is implicated in the fracturing of familial bonds as well as the decline of family lineages within late medieval Italy.” By applying a historical lens to the fractured nature of the Italian city-states in Dante’s time, Lim explores the pernicious effects of envy that is metastasized across generations.

Carson Huang offers a new reading of a favourite Ovidian myth in “Dante and Narcissus: Controlling a Shameful Gaze.” Huang aptly observes that the Narcissian moments in Dante is always associated with shame. The trick is how to move from self-obsession to realisation and ultimately renunciation. Thus, to control desire is to control the gaze.

The ever enigmatic, ever appealing mystical rose at the end of Paradiso is the focus of Faris Joraimi’s eloquent and erudite article. He studies the architectonic structure of the empyrean, its enormous cosmic amphitheatre of concentric rings, and concludes: “Embedded in multiple disruptions of these binary relationships, the Rose is the highest expression of God-in-Creation. The individuation of the flower taking the place of the garden suggests the union of the particular with the universal.”

For Genevieve Ding Yarou, Dante’s rhetoric of ineffability is key to his poetics. Through her analysis of the myth of Medusa, she persuasively argues that the pilgrim’s ineffability is “a moment of petrification that catalysts his Christian conversion towards God.” How does language, fallen and fragmented since Babel, offer a way through the chaos that is Hell?

Like Joraimi, Lu Yi is interested in the incandescent finale of the Paradiso, in particular the incredibly complex three rings. By deploying the work of Arielle Saiber and Aba Mbirika, she brilliantly interrogates how theology and math are united as mimetic sciences of knowledge. And by investigating certain schools of ontology, she explores the question how the study of being is by nature dependent upon yet limited by language itself.

In conclusion, I wish to thank every member of our class (including Jaclyn Tan, Koh Zhi Hao, Michelle Lee, Nirali Desai, Sidharth Praveen, Thaddeus Cochrane), all the contributors, Catherine Sanger, the director of the Centre for Teaching and Learning for believing in this project. Finally I am grateful to the excellent student editors, Carson Huang and Kevin Wong, scholars in their own right—for realizing this project.

Carissa Foo| Lecturer of Humanities (Writing and Literature)

Project

Much discourse on friendship has been centred on male comradeship, citizenship, and homosociality. Women’s friendship, on the other hand, is often framed as temporal, associated with youth and a rite of passage or social education that prepares the woman for society and marriage. Reading women’s literature, students in this course will attend to the nuances and complexities of feminine relations, be they antagonistic or amicable, familial or fraught, in an attempt to formulate for themselves the literary and filmic representations of girlfriendships.

Outcomes

What began as a GoogleDoc compendium of terms and descriptions evolved into a zine, influenced by the early tradition of girl magazine and etiquette manuals, as well as contemporary magazines like Teen and Teenage. Drawing on the wealth of literary source from the course, students worked in pairs to create content that would draw out the essence of girlfriendship as studied in the course. The collaborative aspect of the project also enabled students to depend on and complement the other’s strength, which was an added and lived experience of friendship in the spirit of the class’s aims. Using sketches, illustrations, interviews, quizzes, all inspired from the themes covered in the course, students put together a zine titled, girlgirlgirl. This is accessible online: https://yhu2311.wixsite.com/girlgirlgirl

Valentina Zuin| Senior Lecturer of Social Sciences (Urban Studies)

Project

The TIG enabled me to participate in a month-long hybrid course entitled Designing Technology-Enhanced Experiential Learning offered by the Institute of Experiential Learning in the US. The goal of the course was thinking how to leverage available digital tools and technology to achieve experiential learning outcomes. This class was taught using an experiential learning approach and each student was required to re-design a current course taught or a new one from scratch using the new knowledge acquired through synchronous and asynchronous learning to identify learning outcomes, assessments, rubrics, and develop a proper syllabus. The cohort in the class met weekly and peers played an extremely active role in providing feedback.

Outcomes

During this course I designed an experiential learning class that I was able to teach in a shorter version in collaboration with Prof. Heidi Stella during a week 7 we designed together in September 2020. Further, I have a much clearer understanding about the way in which technologies can be used when students work in teams, and to provide each other feedback, as we experimented with various options during the course. This trip also enabled me to build a network of wonderful faculty interested in experiential learning in top US universities such as MIT and Stanford.

Chelsea E. Sharon | Assistant Professor of Science (Physics)

Project

Problem solving is one of the most important skills that students learn in introductory physics classes, which requires a combination of drawing diagrams, mathematical manipulations, and written words. Students learn these skills best via practice—particularly in small groups under the watchful eye of an experienced tutor. Given the visual nature of physics problem solving, I proposed to obtain several tablet computers so that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, remote students can more effectively work together/with the instructor in class and during office hours. The tablets and styluses effectively work as digital whiteboards with screens that can be shared over Zoom.

Outcomes

During the AY2020/21 offering of General Physics, there was only one student who needed to be remote during the course. The remote student had her own tablet+stylus though, which made her integration with the rest of the class much easier. During each course meeting, she was paired with a physically present student on Zoom, so she could work with them during group practice problem-solving time. Several of the students who were physically present and did not have their own tablets checked out the TIG tablets, and they were able to (1) work much more smoothly with the remote student, and (2) find the tablets so convenient for their own regular note-taking and homework, that many borrowed other college tablets in the subsequent semester (or bought their own, if financially able). As the instructor, working with the remote student over Zoom with tablets made explanations and corrections much easier, since I could share explanatory sketches, demonstrate math steps, and identify mistakes made by the student in real-time, and much more legibly than if we had been drawing using a computer mouse. In addition, between problem-solving sessions, I would use my own tablet for mini-lectures; I could write lecture notes on my tablet (like I normally would on a whiteboard), project the tablet screen for in-person students, and share the screen for the student. The combination of student and instructor tablets very well emulated face-to-face instruction.

In AY2021/22, I had two remote students for a significant fraction of the class: one who had her own tablet, and another who was quarantined in a Singapore hotel for the first ~4 weeks of the semester (I was able to send him a TIG tablet+stylus via his AD). In addition, several students worked remotely on and off due to COVID health scares, and had pre-emptively borrowed some of the TIG tablets as a precaution. The tablets were super helpful in providing flexibility for remote students across the semester, in addition to regularly enabling work and sharing lectures with the remote students. Given the larger number of remote students, I could either pair remote students with other physically present students (as in the previous semester) or group remote students together. Pairing remote students together was nice from a social standpoint since it connected students suffering under similar conditions; however, it was harder for me as the instructor to jump into their breakout rooms and check on progress when I also had a number of physically-present students as well. I had a harder time getting physically-present students to bring computers to class to work with the remote students this time, but that could also just have been an effect of having a smaller number of students in-class (11 physically present this year, as opposed to 20 the previous year). I would recommend other instructors to minimize grouping remote students together and enforcing/incentivising physically-present students to bring computers to class. Using the digital whiteboards were just as useful this AY as they were in the previous.

Overall, while the necessity of stylus-enabled tablet computers was not as widespread as initially expected (since nearly all students were in-person), for the small number of students that were remote, the tablets were extremely helpful. Hybrid instruction is the bane of most professors, and the tablet computers made hybrid teaching nearly as easy as fully remote instruction. As long as the pandemic continues and necessitates remote instruction at times, I would highly recommend tablet computers be made available to students in all math and science courses.

Emily Dalton| Lecturer of Humanities (Literature)

Project

In the summer of 2020, I received a grant from the Centre for Teaching and Learning to enrol in a short online course offered by the Association of College and University Educators (ACUE), entitled “Promoting Active Learning Online.” The course explored strategies for engaging students in varied learning environments, particularly distance and hybrid learning, and enabled faculty participants to discuss and reflect on their own pedagogical approaches. The course took place during the first summer of the pandemic, as the College was preparing for an academic year that would incorporate more virtual and hybrid teaching; thus, it offered a timely opportunity to familiarize myself with techniques for maintaining active student participation in a virtual classroom.

Outcomes

When teaching at the College moved online in the spring of 2020, I was initially quite apprehensive about being able to deliver a similar quality of learning experience as in a physical classroom. While I was fortunate enough to be able to teach in-person classes for most of AY2020-2021, having taken part in the ACUE course made me feel more confident in adapting to changes in seminar format. Moreover, several strategies explored in the course were equally relevant to teaching in a physical classroom. Among these strategies were techniques for introducing more varied discussion formats, crafting better rubrics for assignments, and articulating clearer learning objectives. One of the major emphases of the course was the importance of setting clear expectations and providing regular feedback in an asynchronous virtual environment. Although my own teaching ended up being in person, these conversations refined my understanding of how to construct more precise guidelines for various assignments, and of what kinds of feedback tend to be most helpful to students.

Another valuable skill I learned from the course was how to develop effective microlectures, brief video presentations on a specific topic that can supplement seminar activities and discussions, and that students can then revisit over the course of the semester. This particular unit prompted me to think more carefully about the balance of lecture-style presentations and discussion-based activities in my seminars, and to experiment with ways of inviting students to engage with course content outside of class time. Particularly for courses that require a fair amount of historical contextualisation, shifting some of this to an asynchronous format can free up valuable class time for discussion, and can lead to more informed and insightful conversations.

Throughout the course, participants were given the opportunity to reflect on their own teaching practice and to contribute to discussion forums on specific topics. Faculty taking part in the course came from a wide range of institutions, and having the chance to share ideas and insights with other participants helped broaden my awareness of the challenges specific to different teaching environments. Thanks to these discussions, and to the articles and resources included in the course content, I came away from the experience feeling as if I had a more varied toolkit for designing and conducting seminars. The course content addressed familiar pedagogical values of student-centred teaching and active learning, but having this opportunity for sustained reflection helped me refine the way I put these values into practice.

Francesca Spagnuolo| Lecturer of Science (Mathematics)

Project

When COVID-19 hit and all classes were moved online, I felt completely unprepared: teaching pure mathematics in a strongly interactive format became a huge challenge!

During Summer or 2020, I received the TIG to enrol in the course “Promoting Active Learning Online”, offered by the Association of College and University Educators (ACUE). The course, divided in 5 modules (Microlectures, Notetaking, Collaborative assignments, Active learning Cycle, Facilitate online discussions) helped me developing skills to improve online and hybrid teaching. Moreover, the possibility to interact with other faculty participant from a wide range of institutions and share our pedagogical approaches made the experience complete and opened up my views on challenges in distinct learning environments.

Outcomes

During the summer break of the academic year 2019/20 we were unsure about the future and had to be ready for any shift in teaching format, from full online to hybrid or in person.

I felt the urgency to reorganize my courses to deliver a similar learning experience respect to the past academic years, and that could be easily adapted to any changes of environment.

The strategies and skills acquired from the ACUE course resulted particularly useful during the Fall semester of 2020/21, as most of my courses shifted to hybrid format.

Nonetheless, several techniques learned have helped me even for in-person environment.

The course gave us the opportunity to reflect on our pedagogical strategies, and I was able to improve several of the grading rubrics I already used, as well as make assignment’s guidelines more precise and clearer and introduce a specific weekly rhythm to my courses.

One of the most relevant skills I learned is the use of asynchronous comments to help engage both in-class and online students (useful for all formats). Since then, I have built assignments that involve some asynchronous interaction in several of my classes, particularly in Introduction to Modern Algebra and Geometry and the Emergence of Perspective.

Another strategy I have applied in my classes is the use of videos for microlectures: in particular I have taught students how to use videos, and requested them to present their final projects using this format.

Finally, the section on collaborative assignments allowed me to add different schemes to my list, and use them in hybrid or even in-person classes.

Overall, the biggest outcome from the course could be resumed with the word “adaptability”. Every style, skill or technique I learned can be used for online, hybrid, or in-person teaching: we just need to adapt them (and ourselves) to the new scenario!

Past Grant Recipients (AY 2019/2020)

Nienke Boer | Assistant Professor of Humanities (Literature)

Project

Literary theorists have only recently begun exploring the potential of the ocean, both as environment and as connector, to enrich literary studies. Students in my literature elective Oceanic Frameworks produced a digital and hard-copy compilation of ‘keywords’ for integrating literary studies and oceanic studies, working at the forefront of this new methodological approach.

Each student was responsible for producing content for two to three self-identified keywords, which they rigorously edited in response to blind peer review and feedback from the instructor, similar to the process for academic journals. This assignment thus provides an authentic learning experience that more closely replicates the actual publishing process for academic authors than typical final class assignments. Students had to identify a gap in the existing theoretical literature, choose a keyword that addresses that gap, research and write their entries, perform and receive anonymous peer reviews, integrate the suggestions from their two review reports (one from a peer and one from the instructor), and revise and resubmit their entries. These keyword entries were aimed at a broader, non-specialist audience and have since been published digitally and in print.

Outcomes

The compilation of keywords was published both online (May 2019) and in print (September 2019). We celebrated the launch of the online website in May 2019, with an event that featured two speakers chosen and invited by the students. The final keyword entries are of an extremely high calibre, such that the booklet and website are useful resources for other students and researchers working on oceanic humanities projects. Student reflections on the assignment indicated that it was memorable, enjoyable, and meaningful. I presented on this project at the Fulbright University Vietnam conference on ‘New Approaches to University Education in Asia’ in April 2019. The presentation was framed as a case study approach to adapting assignment types to liberal arts education, in which I argued that traditional assignments in advanced classes in the humanities (longer research papers) might seem to model the work we as academic researchers do, but result in papers that are in almost all cases only read by the instructor (very rarely are undergraduate research papers published). Integrating peer review and a broader intended audience into assignment design allows for a much closer approximation of the academic publishing experience.

Kevin Daniel Goldstein | Lecturer of Humanities (Literature)

Project

The Teaching Innovation Grant helped facilitate a semester-long project in which fifty-three Literature and Humanities I students produced a compendium of literary terms reflecting the diverse linguistic and cultural traditions of our syllabus: Sanskrit, Greek, Chinese, Mandekan, Arabic, Malay, and Italian. Working in groups of three, with careful scaffolding, the students researched and wrote multi-page entries on eighteen assigned terms, then presented the findings to their colleagues. I subsequently produced and printed digital copies that will provide a valuable resource not only for future Literature and Humanities courses but for world literature courses more generally.

Outcomes

These terms expanded my students’ critical vocabulary, becoming part of our collective discourse, both particular to a given tradition and potentially universal. For example, students productively applied the Sanskrit term rasa (emotional effect) both to Valmiki’s Ramayana and to texts beyond South Asia, such as Homer’s Odyssey: rasa helped to frame our discussion of Odysseus’ arrival in Ithaca, bringing to the fore the effect of the passage in a way that English critical vocabulary sometimes limits. These cross-cultural applications also prompted rich class discussions on the cultural work of interpretation, translation, literary universalism, and difference.

Due to the eurocentrism of standard volumes of literary terms in English, literature courses, even world literature courses, rarely include the study of non-European literary terms. Instead, the Western critical tradition dominates the process of interpretation, literally and figuratively setting the terms for textual analysis. Decolonizing the curriculum is not solely a matter of what texts we read, but how we read them. Compendia like this one have the potential to galvanize educators and scholars to rethink how volumes of literary and rhetorical devices are written while offering a new tool to decolonize pedagogy in the humanities and beyond.

Matthew D. Walker | Associate Professor of Humanities (Philosophy)

Project

The ‘Mellon Philosophy as a Way of Life Network’ (https://philife.nd.edu/) is a new initiative based at the University of Notre Dame and supported, in part, by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The network consists of philosophy faculty – from the U.S. and abroad – interested in introducing students to traditions that approach philosophy in a distinctly practical way. The aim is to enable students to encounter philosophy not merely as isolated theory, but as an “art of living” in which theoretical reflection can enhance one’s ability to live well.

My TIG enabled me, as a network member, to participate in the inaugural ‘Philosophy as a Way of Life’ workshop at the University of Notre Dame in June 2019. At this event, which took place over five days and which was attended by dozens of faculty from around the world, I attended sessions and workshops, and shared my own experiences, concerning the following stated themes: “(1) Developing assignments that help students to connect philosophical arguments with their own day-to-day decision-making; (2) Equipping each other to teach texts and traditions from different cultures that offer visions of the good life; (3) Building diverse, collaborative learning communities and peer-led discussions around philosophy as a way of life themes; (4) Promoting research into philosophical approaches to the good life, especially on topics that are likely to translate to philosophy curricula.”

Outcomes

I benefitted enormously from learning about the many exciting assignments that other instructors have been developing to bring philosophy to life, both in the sense of making philosophy exciting and in the sense of showing philosophy’s relevance for living. On the basis of my experience at the workshop, I introduced a new assignment, and reconceived an old assignment, for my sections of Philosophy and Political Thought 1, which I taught in Semester 1 of AY2019-20. The workshop also gave me ideas for new assignments to explore in my Philosophy as a Way of Life elective, which I will teach again in Semester 2 of AY2020-21. Although the second Philosophy as a Way of Life workshop for 2020 was canceled on account of the COVID outbreak, I remain in touch with other network members via a Facebook group.

In January 2020, another network member, Bart Van Wassenhove (University Scholars’ Programme, NUS), and I shared our experiences from the workshop and our classes. We hosted a lunchtime event – entitled “Living Ideas: Immersive Assignments and their Learning Outcomes” – at Cinnamon College in UTown. We discussed our use of “immersive assignments” in our courses, how those assignments promoted course aims, and how we might refine those assignments in our future teaching. Faculty from Yale-NUS and various schools around NUS attended our session.

Stanislav Presolski | Assistant Professor of Science (Chemistry)

Project

Accelerated Organic Chemistry is a course on the structure, properties and reactivity of carbon-based molecules, which constitute most of our natural and artificial surroundings. While ‘ball-and-stick’ model sets have been used since the 1860’s by pioneers in the field, they can only capture the relative position of atomic nuclei in space, omitting the all-important electron density that is involved in chemical reactions. That is why chemists use molecular simulation software to model electron orbitals, but those computer visualizations lack the materiality of physical objects and thus remain peripheral to students’ learning. Our attempt to bridge that gap was supported by a Teaching Innovation Grant (TIG), which allowed us to purchase a 3D printer and invest the necessary time and resources into this project.

At the very beginning the course and the accompanying Organic Chemistry Lab, students were introduced to Chem3D – an extension package to the industry-standard ChemDraw software. Several assignments required its use to predict trends in reactivity, while at the same time classroom discussions were used to remind students of the quantum mechanical reasoning behind the rules of thumb they were learning from the textbook. Later in the semester, when the complexity of the reactions could not be properly explained by flat drawings on the board anymore, 3D printed models were used as instructional aids to a great fascination and appreciation by the students.

Outcomes

The culmination of this project was a final presentation in which students used 3D printed molecular models to rationalize the complicated reactivity of the compound they had prepared as part of the Advanced Synthesis lab. Niki Koh from Arts and Media was instrumental in overcoming the severe obstacles presented by the impossibility to directly print from the computer programs used in chemistry. He used a dedicated 3D modelling software to manually recreate the complicated shapes that we had to print to make this venture a success. Many molecular orbitals tend to be quite similar to one another, so in the future we can not only use the models that have been printed, by tapping into the small library of shapes that we created and modify them slightly in order to illustrate the reactivity of completely different molecules. Therefore, the 3D printer purchased with the TIG can be even more readily used in the future to enhance chemistry teaching and learning at Yale-NUS.

Valentina Zuin| Assistant Professor of Social Sciences (Urban Studies)

Project

The TIG enabled me to travel to Williams College and Swarthmore College in September 2019, to learn how other liberal arts colleges conceptualize, fund, execute, and improve experiential learning in their institutions.

I met a total of 16 people, including 2 directors of the centres that support experiential learning at Williams and Swarthmore. I also interacted with the director of the Centre for Peace and Global Citizenship at Haverford College.

Outcomes

During my trip, I identified thirteen different models that are used by faculty at Swarthmore and Williams to deliver experiential learning in the curriculum and their best practices in designing and implementing experiential learning in the curriculum. I plan to start experimenting with some of these models at Yale-NUS, in one of my elective classes.

This trip also enabled me to build a network of junior and senior faculty stakeholders interested in engaging students in service and experiential learning in a number of different disciplines and across them, and whose wealth of skills and experience can be tapped in the future. I am in discussion with one of the colleagues at Swarthmore about opportunities to teach a class with an experiential learning component together.

Past Grant Recipients (AY 2018/2019)

Sandra Field | Assistant Professor of Humanities (Philosophy)

Project

Political philosophy can be doubly abstract for students in Singapore. First, some of the classic works in the field are deliberately removed from the messiness of real life for the sake of conceptual clarity. Second, the reality to which the classic works refer are American or European, and not Asian. My project was to structure my courses to overcome this abstraction, and to use theory to speak to real-world problems. Students wrote an opinion piece, drawing on the theories of the course but applied to a real-world topic of their choosing. The pieces were written for a broader audience of readers, and were displayed on a public website, read by the college community, and incorporated into teaching for subsequent cohorts of the courses.

The Teaching Innovation Grant allowed me to provide an optimal showcase for students’ work. I engaged a professional web developer to design an aesthetically beautiful and functional webpage. The TIG also allowed me to engage two student photographers to provide images for the site and a student associate to promote the website and for research assistance.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the website Equality & Democracy. Students in each new iteration of the course have to negotiate with the arguments of the earlier groups, as they work towards adding their own new contributions to the site.

Beyond the website, the project snowballed into further pedagogical research and development, culminating in a publication in the Asian Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (December 2019). I presented my research at the 8th Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Conference (September 2018); on the strength of this presentation, I was invited to run a seminar for faculty as part of the NUS CDTL Continuing Professional Development Programme (April 2019). The final publication included the findings of an IRB-approved pedagogical survey of student experience (January 2019).

Student work from the website has been favourably received. One student’s piece received an Honourable Mention in the Undergraduate Public Philosophy Award of the Blog of the American Philosophical Association, and was then republished on the APA’s Women in Philosophy blog.

Malcolm Keating| Assistant Professor of Humanities (Philosophy)

Project

As a recipient of the Teaching Innovation Grant in AY 2018/19, I was able to design and implement a survey to study how students taking philosophy electives think about philosophy before and after their courses. The goal was to gather information on why students decide to continue in philosophy courses or declare a major, as well as how they think about the importance and relevance of philosophy for their own lives and careers. As part of the grant, Kristie Miller and David Braddon Mitchell (both from the University of Sydney), who have worked on similar empirical studies of philosophy students in Australia, came to campus to help with survey design.

Outcomes

I am analyzing the results of the survey with the help of Assistant Professor Paul O’Keefe from the Psychology department at Yale-NUS. While it is too early to make any assessments about the student body at Yale-NUS College, information from the survey may form the basis for hypotheses about why students choose a major in philosophy (or do not), which could be investigated further by the philosophy faculty. The TIG has given me an opportunity to consider more carefully the interactions between student demographics, classroom experience, and major choice.

Heidi Stella Therese| Associate Professor of Humanities (Writing, Literature)

Project

Reading Dantes Divine Comedy for the first time is a confounding and exhilarating experience for anyone. Confounding because there’s so much stuff that you need to know to understand the poem; exhilarating because Dante presents to you the sublime and terrifying grandeur of his cosmic vision. The only prerequisite for reading is an experience of the human condition. So anyone can pick up the poem and get something out of it.

In the first semester of the 2015-2016 academic year—the third in Yale-NUS’s young life—I taught a course on the Commedia. It was my first time teaching my own seminar, the first time Dante was taught at the College, and, to my knowledge, the first time in Singapore. With the TIG, I was able to transform six student essays from this class on Dante into The Dante Journal of Singapore.

I was, as it were, the Virgil to a group of ten Dantes. For three months, for three hours a week, we read, carefully and intensely and philologically, every single word of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. We paid special attention to the historical, intellectual and social world of the European Middle Ages and the fraught legacy of the classical tradition (we also read the entirety of Virgils Aeneid, chunks of Ovid and the Bible along the way). We discussed theology and revelation, the state of souls in the afterlife, the primacy of poetry as an intellectual and spiritual activity, the nature of art and beauty, the relationship between pagan myths and Christian mysteries, and the medieval encyclopaedia of classical learning and medieval religious doctrine.

I am honoured to present six essays of the highest caliber in The Dante Journal of Singapore, which now exists in print and online thanks to the generous funding of the TIG. The essays in the journal represent the students travelogue, by now a two-year journey. These are all pieces of undergraduate research that make a real contribution to the 700-year old tradition of Dante scholarship

Outcomes

This publication allowed me to build an” authentic learning experience” for my students. Whereas most final papers in class are quickly written and then summarily hidden away and forgotten, we worked on them, refined them, and made them exponentially better than any end-of-term paper. By making them revise and then showcase to the public their hard work, the contributors learned the process of journal submission, revision, responses to the editor and peer review. Student editors also learned the process of running a journal. These are essential skills not only for the students who wish to go on to graduate school, but also for any professional field involving writing.

Robin Zheng | Former Assistant Professor of Humanities (Philosophy)

Project

This Teaching Innovation Grant supported the first run of the Oppression and Injustice (YHU2280) Class Textbook Project. YHU2280 is an entry-level Philosophy course focusing on theories of resisting injustice, developed by and for oppressed groups. The course examines Black feminist thought in the first half, and postcolonial Latin American philosophy in the second.

Students as a class were assigned to jointly write their own textbook on the course material. In doing so, they encountered a number of issues explored in the readings: the challenge of theorizing about liberation in an non-exclusionary, jargon-free way, of reconciling alternative ways of knowing with a dominant epistemology that effectively functions as a kind of academic gatekeeping, and of organizing a diverse group of participants toward a shared long-term goal. The class was responsible for all stages of textbook production: selecting a target audience, planning and organizing the overarching structure of the text, writing individual chapters, and editing the final manuscript. Through the project, students needed to understand themselves not just as consumers but also producers of knowledge, to recognize the authority and responsibility they possess in virtue of their position in the academy, and to critically reflect on processes of knowledge production that form the basis of their own education.

The Class Textbook Project also represented a novel form of summative assessment for philosophy courses, which traditionally consists of writing argumentative papers. Yet much philosophy seeks also to explain and critically describe the world, e.g. by creating new concepts and terminology to capture phenomena that have previously gone unnoticed or unanalyzed, in the service of guiding political action in the world rather than as a mere theoretical exercise. The Class Textbook Project enabled students to undertake an authentic learning process in keeping with these aims, in which they were asked not only to acquire mastery of key philosophical concepts, but also to write clearly, concisely, and accessibly for a broad audience. By producing a textbook showcasing historically underrepresented voices with the intent of educating actual readers, they exercised these analytical and writing skills in service of the larger real-world project of overcoming injustice, which was the central subject matter of the course.

Outcomes

30 hard copies of the textbook were disseminated throughout the college. An electronic PDF version was also licensed for the public domain and made available here. Students gained from the reality of seeing their work published in a hard copy text.

The grant also enabled me to present the project at two pedagogical conferences where I contributed to the academic discourse on teaching this material: the 22nd American Association of Philosophy Teachers Workshop-Conference on Teaching Philosophy in Greensboro, N.C. (USA), and the Athens Institute for Research and Education 6th Annual International Conference on Humanities & Arts in a Global World in Athens, Greece. I received valuable feedback on how to improve the project and make it sustainable for the future, as well as potential ways of adapting the project to a variety of different courses, institutional contexts, and student demographics.

Chan Kiat Hwa | Assistant Professor of Science (Chemistry)

Project

My project sought to model “YSC2225: Physical Chemistry” on the guiding principles of Problem Based Learning (PBL), a student-centered teaching pedagogy designed to help students become more independent in their learning. PBL uses real-life situations and problems that allow students to acquire new knowledge through the process of identifying relevant issues and solving each issue in a systematic way. Due to its emphasis on small group learning, it is best suited for small class sizes, where students have access to a high level of instructor attention.

The Teaching Innovation Grant enabled me to conduct a semester-long study on the efficacy of PBL in my Physical Chemistry elective. Students in the elective were assigned into groups to solve complex real-life problems building on straightforward questions that tested course concepts. Further, the lab component was designed as a semester-long real-life research problem that would have to be solved by the student through discussions with their classmates and the instructor. To monitor student responses, a series of surveys was designed and administered over the course of the semester.

Outcomes

The students’ responses show that they found physical chemistry concepts, although not immediately apparent, are relevant to real-life situations. The laboratory experiments were also generally successful in helping the students to grasp the concepts in class. Students were more open to collaborating with each other in the lab than in the classroom. However, they tended to approach the instructor for help instead of taking the initiative to troubleshoot amongst themselves. Although the laboratory experiments were pitched as an opportunity for the students to troubleshoot and increase their resilience to failure, this was not well received by students. As such, their team-specific problem-solving skills did not perceptibly improve at the end of the semester.

Considering the time limitations of a 5 MC course, which allots students 12.5 hours per week (inclusive of lectures, seminars, laboratory sessions, assignments and self-study) for that particular course, students may not have felt it economical to allot more of their time towards team-based problem solving when faced with the additional need to study coursework individually, as well as other responsibilities for other courses.

The effectiveness of PBL as a teaching approach for Physical Chemistry at Yale-NUS specifically is hence debatable. PBL contains numerous moving parts – syllabus material, amount of time available for self-study, student life culture, facilitator competence – that have not been investigated individually and rigorously at present. PBL as a teaching method within Yale-NUS for Physical Chemistry should hence be reconsidered, or, at minimum, redesigned and executed with close supervision and collaboration by the instructor with other facilitators who have had more experience with implementing PBL successfully. This allows educators to identify which aspect of PBL is the most effective and worth using in their own classrooms.

Nicholas Tolwinski | Associate Professor of Science (Life Sciences)

Project

This project exposed students to the global science community sharing process. Through the TIG, I was able to bring three undergraduates for whom I have supervised senior capstone projects to participate in the 59th Annual Drosophila Conference in Philadelphia. My students and I gained a wealth of insights regarding the latest developments in Drosophila research, ranging from molecular cell biology and neuroscience to evolution and genetic tools. We attended several panels concerning pedagogical tools and strategies for science education and were able to share about the Yale-NUS experience with multiple interested parties. The experience also created opportunities for authentic learning where by the students had professional interactions with the global scientific community. Here, students were mentored on their research as they shared about their capstone research and gained valuable insight and learning from their respective feedbacks in the process.

Outcomes

Through this conference, I got the opportunity to discuss pedagogical tools and strategies with professors from around the world and gain valuable feedback regarding my own personal teaching style. I hope to implement some of these suggestions in my future courses and share these insights with my colleagues at Yale-NUS. Specifically, I am excited to explore the possibility of using citizen-science platforms in the common curriculum as a fun way to introduce undergraduates to science research. Through the various panels, lectures, and interactions with my colleagues, I learnt about several interesting new discoveries and lines of research that I hope to integrate into my future Genetics and Molecular Cell Biology courses. It is my hope that drawing upon such innovative research in my lectures will make the theory more exciting and relatable for the students, inspiring them to think more deeply about the practical applications of the lesson content.

Finally, from their exposure to the broader scientific community, my students gained valuable insights and feedback for their capstone projects that was directly translated into the excellent quality of their final presentations. The students were also able to formulate concrete next steps in the development of their research ideas, with the aim of publishing their results in the near future. They will be sharing their takeaways from this conference with their underclassmen and therefore helping the larger Yale-NUS community improve the quality of future research projects. Seeing all the benefits that have arisen from this opportunity, it is my hope to expose more students to such academic environments in the future.

Additionally, the students who went on this conference have begun the process of transmitting their findings, both about academia and academic conferences and about the specific experience of conducting their research projects. Through doing so, these students will work to build a longitudinal base of knowledge to be transmitted through successive years of students which will facilitate learning outside the classroom.

Keng Shian-Ling | Former Assistant Professor of Social Sciences (Psychology)

Project

The Yale-NUS Teaching Innovation Grant enabled me to invite Dr. Judith Simmer-Brown, Professor of Contemplative Education and Pedagogy from Naropa University in Colorado, USA to offer a series of lectures and workshops on contemplative approaches in higher education on our campus. These events included: a public lecture on methods for incorporating contemplative methods in the classroom (‘First-Person Inquiry in Contemplative Education: Methods for the Classroom’), an academic contemplative writing workshop (‘Words and Sense: Contemplative Academic Writing’), and an open classroom session involving the demonstration of contemplative pedagogy approaches with students. Additionally, I chaired a panel session on contemplative pedagogy in higher education, with Dr. Simmer-Brown, Dr. Parashar Kulkarni, and Ms. Ho Gia Anh Le as panelists.

Outcomes

In part thanks to support from the Dean of Faculty, one exciting outcome arising from Dr. Simmer-Brown’s visit is the emergence of the Yale-NUS Mindfulness in Education Initiative, which consists of a series of ongoing mindfulness practice sessions offered for faculty members and staff at Yale-NUS College since April 2019. The sessions aim to support faculty and staff members in cultivating mindfulness and contemplative practices in their daily life, the classroom context, as well as in the context of writing and research. The sessions are facilitated by Ms. Ho Gia Anh Le, a mindfulness educator and former lecturer at the National University of Singapore (NUS). A core group of faculty members regularly attended the sessions, and participants expressed appreciation for the opportunity to co-create a safe and supportive space where they engage in self-care and explore the incorporation of mindfulness practices into their personal life, teaching, and research.

Overall, these events were well received on campus. I benefitted greatly by learning from Dr. Simmer-Brown’s expertise and experience in contemplative teaching. In particular, I find her four levels of contemplative engagement framework (embodiment of mindfulness by the instructor, creation of a community learning environment, incorporation of contemplative teaching methods in the classroom, and complete curriculum innovation) to be immensely helpful in thinking about contemplative education more broadly. Such a framework is consistent with Yale-NUS’ liberal arts and sciences curriculum, which draws from diverse intellectual traditions and modes of learning to benefit students. Within this initiative, there is now a growing community of faculty members dedicated to incorporate mindfulness and contemplative approaches into teaching and learning at Yale-NUS.

Jean Liu | Assistant Professor of Social Sciences (Psychology)

Project

This project exposed students to the global science community sharing process. Through the TIG, I was able to bring three undergraduates for whom I have supervised senior capstone projects to participate in the 59th Annual Drosophila Conference in Philadelphia. My students and I gained a wealth of insights regarding the latest developments in Drosophila research, ranging from molecular cell biology and neuroscience to evolution and genetic tools. We attended several panels concerning pedagogical tools and strategies for science education and were able to share about the Yale-NUS experience with multiple interested parties. The experience also created opportunities for authentic learning where by the students had professional interactions with the global scientific community. Here, students were mentored on their research as they shared about their capstone research and gained valuable insight and learning from their respective feedbacks in the process.

Outcomes

As the key outcomes of the TIG, I created the following two websites:

Website 1: The Science of Love thescienceoflove.org

In AY2018/19, I developed a new course on the science of love (‘Topics in Psychology: Love in an Age of Technology’). As the primary assignment, students spent the semester creating an online toolkit supported – through backend web development – by the TIG. To construct the toolkit, our class identified meta-analyses and review articles discussing how romantic relationships are formed. In seminars, we then debated the current state of the evidence, and the extent to which these findings inform the online dating industry. The final toolkit, modelled after ‘What Works’ websites in the UK, was then launched at a public event for CEOs of dating platforms, government agencies, and the academic community.

Website 2: A College Portfolio of Nudge Projects

As a longer-term project, I have also developed a template for a second website supported by TIG funding. This website will showcase home-grown projects where our students apply psychology to optimize policy outcomes. To date, we have run eight such projects through a psychology course (Lab in Psychology and Public Policy), and five other projects through capstones, independent study modules, and extracurricular work. This website wil be launched when a critical mass of projects has been reached.

Paul A O’Keefe | Assistant Professor of Social Sciences (Psychology)

Project

My research has shown that the beliefs people hold about the nature of interest have important educational consequences. Compared to people who believe that interests are inherent and relatively unchanging (a fixed theory), those who believe that interests can be developed (a growth theory) tend to express more interest in new or different topics, and they tend to maintain a new interest even when it becomes difficult to pursue. In a recent field experiment with first-year college students, I also found that a brief growth-theory intervention (vs. control) has these educational benefits up to two years later. Given the success of this intervention, I wanted to conduct another and improve upon it by examining the potential of a growth theory of interest to increase student well-being.

Outcomes

The Teaching Innovation Grant helped me prepare for this study by funding my participation at the International Conference on Motivation in Aarhus, Denmark. There, I presented my intervention research and met with leaders in the fields of motivation science and psychological interventions. Those meetings were integral to the design of my current intervention study, which will continue to run through the academic year. I hope to find that a growth theory of interest helps students cope with the difficulties they face in courses outside of their pre-existing interests, and helps reduce stress during their first year of college.

Past Grant Recipients (AY 2017/2018)

Andrew Hui Yeung Bun | Associate Professor of Humanities (Literature)

Project

Reading Dante’s Divine Comedy for the first time is a confounding and exhilarating experience for everyone. Confounding because there is so much one needs to know to understand the poem; exhilarating because Dante presents one the sublime and terrifying grandeur of his cosmic vision. The only prerequisite for reading is an experience of the human condition. So anyone can pick up the poem and get something out of it.

In the first semester of the 2015/16 academic year — the third in Yale-NUS’ young life — I taught a course on the Commedia. It was my first time teaching my own seminar, the first tame Dante was taught at the College, and to my knowledge, the first time in Singapore. The TIG enabled me to transform six student essays from this class on Dante into The Dante Journal of Singapore.

I was, as it were, the Virgil to a group of ten Dantes. For three months, for three hours a week, we read, carefully and intensely and philologically, every single word of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. We paid special attention to the historical, intellectual, and social world of the European Middle Ages and the fraught legacy of the classical tradition (we also read the entirety of Virgil’s Aeneid, chunks of Ovid and the Bible along the way). We discussed theology and revelation, the state of souls in the afterlife, the primacy of poetry as an intellectual and spiritual activity, the nature of art and beauty, the relationship between pagan myths and Christian mysteries, and the medieval encyclopaedia of classical learning and medieval religious doctrine.

I am honoured to present six essays of the highest calibre in The Dante Journal of Singapore, which now exists in print and online thanks to the generous funding of the TIG. The essays in the journal are all pieces of undergraduate research that make a real contribution to the 700-year old tradition of Dante scholarship.

Outcomes

This publication allowed me to build an ‘authentic learning experience’ for my students. Whereas most final papers in class are quickly written and then summarily forgotten, we worked on them, refined them, and made them exponentially better than any end-of-term paper. By making them revise and then showcase their work to the public, the contributors learned the process of journal submission, revision, responses to the editor and peer review. Student editors also learned the process of running a journal. These are essential skills not only for the students who wish to go on to graduate school, but also for any professional field involving writing.

Eduardo Lage-Otero | Senior Lecturer of Humanities (Spanish) & Deputy Director of Language Studies

Project

Language instruction is a robust programme at Yale-NUS College, covering Chinese, Spanish, and several other languages. The Teaching Innovation Grant offered me resources to visit Language Studies centres in the United States to learn about their course-sharing initiatives and find ways to enhance our programmes at Yale-NUS.

At Yale University, I met with colleagues at the Centre for Language Studies (CLS) to strengthen our ongoing collaboration on language instruction via teleconferencing. I also visited the Department of Spanish and Portuguese to learn about how they accommodate growing numbers of students taking Spanish, and how they create opportunities for students to practice Spanish outside the classroom. I also attended a symposium on community-based language education hosted by CLS where I learned about creative ways to extend language learning beyond the classroom and weave community resources into the curriculum. I also visited the Yale Centre for Teaching and Learning to learn about their initiatives to enhance teaching across the university in face-to-face and online settings.

Following this, I travelled to the Language Centre at the University of Chicago, where I learned about their course-sharing initiative within the Big Ten Academic Alliance. Subsequently, I travelled to Madison to visit the University of Wisconsin Collaborative Language Program and met with its programme director, Lauren Rosen, who has been working on tele collaborations for over 20 years, to discuss the structure and evolution of her programme. We collaborated on a panel presentation, ‘How collaboration builds sustainable programs: Growing and diversifying language offerings on a dime’, for the June International Association for Language Learning Technology (IALLT). The presentation highlighted several models of enhancing and increasing language study opportunities via collaborations while discussion the implications of this type of effort for the institutions involved. While at Madison, I was also able to participate in a Teaching Symposium at the University of Wisconsin where teaching and learning theories and practices were discussed.

Outcomes

I was able to meet with colleagues working in related fields, and who have undertaken similar or more ambitious programmes. I continue to reflect on the Yale-NUS College language programme and adapt some of what I have seen to our Liberal Arts context here in Singapore.

This project also enabled me to present my work at an international conference on our practices at Yale-NUS. As we continue to expand the language opportunities available to our students, this type of collaboration and idea-sharing will be crucial to ensure that we meet our intended learning outcomes.

Philip Johns | Senior Lecturer of Science (Life Sciences)

Project

The TIG enabled me to better understand the use of a portable sequencing device, the Nanopore Min-ION, for teaching and research applications. Sequencing technology has revolutionised how people think about genetics, ushering in the age of genomics. The challenge is that most equipment used to generate DNA and RNA sequences are large and very expensive. Sequencing becomes something of a black box: we send off samples and wait weeks or months to get DNA and RNA sequences back. For some applications, especially in teaching and in field research, being able to generate genetic sequences on-site and in real time is not only convenient but also instructive. The Min-ION stands out from other sequencers due to its portability and affordability, and addresses the demands of teaching and field research.

The goal of this project was to generate protocols that students could use in modules for in-class projects, so they could analyse sequences on-site and in real time. The Min-ION and other similar devices could be an integral part of science modules at Yale-NUS College.

Outcomes

My students and I were better able to understand the use of the Min-ION for our work. Based on our protocol, the results can be further developed in a few directions — e.g., to ‘barcode’ samples with which we can identify species by DNA sequence, or to measure gene expression of genes of interest. Either of these applications can be used in teaching field-based courses with a genetics or genomics component, such as a Genomics LAB in forests, or a Conservation Biology course built around ecological genetics.

David Andrew Smith | Assistant Professor of Science (Mathematics)

Project

This project sought to address some of the shortcomings of traditional peer feedback models by implementing an online and in-class peer feedback model in Proof. Proof is an MCS module pitched to second year students that serves as a gateway to higher level modules in mathematics, computer science, and statistics. In this module, the potential drawbacks of peer assessment are magnified, as the likelihood of a student providing valuable feedback is low, especially towards the beginning of the module.