Best Practices in the Classroom

Managing a classroom is one of the key aspects of teaching excellence – how do we gain our students attention and pique their interest in the classroom? How do we ensure that they are able to learn and retain knowledge? How can we best communicate our expectations to students? These are questions that will be answered by the following tips and resources on managing your first day of class, leading discussions, enlivening your classroom and more.

A successful first class sets the tone for all future classes. Three things that can make this happen are:

- Learning to correctly pronounce students’ names to create an inclusive environment in a diverse classroom

- Making good use of the first few minutes

- Clarifying course expectations

- Getting a sense of where students are

1. Learning to correctly pronounce students’ names to create an inclusive environment in a diverse classroom

In various intercultural surveys of students, some students have highlighted that they feel that some faculty members cannot pronounce their names and therefore do not call on them. Although we are sure that many faculty members have their own, effective ways of learning names, we thought we would provide support with this simple method that some people may find helpful. Using these card is not required. If you need more name cards, they can found in the stationery supplies cabinet in the respective RCs and Co-Learning Lounge. If you have more than you need, you can return them.

Learning students’ names signals your interest in their performance and encourage student motivation and class participation. You can ask students to include preferred pronunciation and how they prefer to be addressed as well. Some students may choose to display which pronouns they prefer to be addressed by: some people prefer the conventional “he” or “she,” (his/her) but some may have adopted alternatives like “they,” “them” and “theirs” as personal pronouns.

2. Making good use of the first few minutes

As we all know, first impressions are important. Don’t let a poor introductory session tune your students out. Here are some tips for getting your class hooked from the very first session:

Give the course a face.

The first few minutes are a great opportunity to secure student interest. Students need to feel your personality and enthusiasm about the class, to associate the course with a real person who is curious, excitable, and passionate like themselves.

Keep it warm and cool.

A useful way for you to introduce yourself is to weave in a balanced number of warm points—things that show how your experiences or personality will inform this course—as well as cool points—things that are more serious, setting the expectation and tones for the class.

Something curious and something personal.

You may share with students how something personal relates to their intellectual curiosities, and have students share how they anticipate engaging with the materials of the course would relate to their living experience. This might encourage a deepening of learning goals with desired personal outcomes, which would in turn facilitate not just a better attitude towards the class, but also retention as they apply what they know to how they live.

3. Clarifying course expectations

This involves bringing students through the overview of the course, what they can expect to learn, and the kinds of topics they look forward to engaging with. It is also a great time to ask for feedback and a general sense of how the class is feeling towards the course. If changes are necessary, it is still early enough to make adjustments to the syllabus. Considering student feedback also makes them feel more involved in their own learning. If you decide to make adjustments as per the feedback obtained, make sure to let your students know what you’ve changed.

4. Getting a sense of where students are

College students enter the classroom with their own ideas of how things work. It will be helpful to test the waters and see where they are in terms of the subject matter at hand. A kickoff test will help you understand more about your class. This test can include factual elements to see how students differ in terms of content exposure. You can also take this time to learn about how your students perceive certain issues, as well as their motivations for taking the course.

For more information, you can read through this article written for Carnegie Mellon University, which examines the impact of students’ prior knowledge, intellectual development, cultural background and general experiences on learning.

Check Out the Room & Imagine the Space

- What is the set up? How can you alter it to meet your needs?

- What are the limitations? Contact the Faculty Affairs Office for markers, erasers, and other tools. Contact IT (yncit@yale-nus.edu.sg) for technological assistance and Infrastructure (infra@yalenus.edu.sg) for repairs to the physical space.

- What are the possibilities? Consider how different configurations could achieve your teaching goals, foster the kind of participation and discussion you want, amplify student learning.

- Where will you stand or sit and how will that impact course dynamics? How might your positioning generate more hierarchical versus egalitarian participation norms. Which is more desirable given your course goals, classroom diversity, and desired persona?

- How will the use or non-use of laptops disrupt or facilitate course goals in this space?

Communicate Course Goals and Prepare to Answer Common Questions

- Share your syllabus with course timing, location, and required materials.

- Prime students with your expectations, course goals and expected learning outcomes.

- Help students plan for a successful semester by providing paper, exam, and assignment timelines. – Communicate participation and attendance standards, grading policies, and expected behaviours.

- Anticipate student questions and find answers: students may want you to add them to the roster, to know add-drop deadlines, prerequisites, etc. Many of these questions can be answered on the faculty portal (portal.yale-nus.edu.sg) under ‘Registry’ and ‘Teaching and Learning.’

- For syllabus template visit: https://portal.yale-nus.edu.sg/teaching-preparation-and-delivery/syllabus-template/

Anticipate Student Expectations and Needs

- Given our highly diverse student population, what additional steps can you take to craft and communicate course goals? Consider how this population might differ in their prior experiences and expectations from students you have taught elsewhere. How might you capitalize on the Common Curriculum experiences? What can you do to ease the transition for yourself and for your students?

- Are there forms of ‘common knowledge’ in your own cultural context which might need to be made more explicit in a diverse classroom?

- Consider what you want to know about your students’ prior experiences, comfort zones, and background in order to plan the course. How can you solicit that information early in the semester (e.g. through ice-breaker activities, by asking them to fill in a questionnaire either anonymously or openly, through some ungraded skills assessment)?

Plan Your Persona, Formality, and Accessibility

- How you dress, what you say, and your general manner on the first day will set a tone for the semester. Making these choices deliberately will help establish your desired rapport with students. Decide what kind of persona you feel comfortable with and what kind of authority you want to project in the classroom. From there you can make choices about how to introduce yourself and dress on the first day, what norms to communicate about email and in-person contact, and generally how to present yourself to your new students

- It is generally easier to open up access, or move from formality to informality, over the semester than the reverse. You may want to set a more formal tone at the beginning even if you intend to loosen up later in the term.

- Anticipate and communicate boundaries that are important for you as a professional (e.g. if you know you do not check or respond to emails over the weekend communicate that upfront so students can plan accordingly).

THE FIRST DAYS OF CLASS:

Fight Butterflies with Preparation

- Have all print outs and materials ready the day before, especially if you are new to this campus and technology.

- Arrive early, arrange chairs, write relevant course information on the board or on slides

- Upload slides to the course Canvas sight in advance if that is in line with your teaching approach – Greet students as they arrive to help you learn names, project confidence, and establish rapport.

Model Desired Course Dynamics and Practices

- Whatever behaviours you expect, or activities you plan to emphasize, during the semester, start doing it on the first day of class. e.g. If punctuality is important to you, start the first class on time to set the tone for subsequent weeks. If you want them to talk to each other, and not only to you, insist they learn each other’s names and direct comments to each other on the first day.

- It can be tempting to spend the entirety of the first class reading through the syllabus and explaining administrative details. If you expect the course to run on student participation and initiative, try to have them participate in discussion during the first day to establish firmly that they need to contribute actively to the course.

- If during break-out groups or in seating patterns you notice student self-segregation by cohort, sex, ethnicity, or other factors, and if you feel comfortable doing so, consider asking students to reorganize themselves. Alternatively, consider assigned but rotating groups or seating assignments.

Get Students Excited and Organized

- Link an introductory ice breaker to course material. Instead of asking the traditional questions (name, class year, hometown) consider asking students to share a fun fact, an opinion, or an aspiration linked the course material. (E.g. in an art history class ask them to share what artist they would choose to paint their portrait and why). Or have them propose and ask the class questions about each other and of you.

- The beginning of a course can get bogged down with administrative detail. Try to make room in the first class to teach students something interesting they did not know before or to raise a particularly controversial aspect of the course material.

- Highlight deadlines and other key items so students can get organized and employ effective time management habits. Clarify the assignment or deliverable expected for the next class meeting.

Help Students Help Themselves Succeed

- Many students will be too shy or ashamed to admit feeling lost, confused, or overwhelmed by new material. Develop ways authentic to you to assure them these reactions are a normal part of learning, and guide them in strategies to overcome these obstacles (asking for peer support, faculty office hours, Writer’s Center, Associate Dean, peer tutoring programme, etc.). Explicitly communicate that you are committed to helping students succeed.

- Communicate what you expect students to do when they are feeling lost (or insufficiently challenged), and what they can (and cannot) expect from you when they ask for help. Many students may have had an easy time succeeding in school before entering college, and do not know how to handle setbacks. Give them explicit suggestions for succeeding in your class (e.g. attending office hours, close reading techniques, drafting, keeping up with current events).

- Hang around after class to talk to students with special concerns or needs, who often will not feel comfortable asking their questions in front of peers.

Solicit Feedback

- Mid-semester feedback is great, but it can be helpful to solicit feedback even earlier. Consider prompting students to submit anonymous comments through Canvas, or write for two minutes on their main ‘take-away’ lessons at the end of each class for an ungraded ‘check-in’ submission (this also helps them consolidate knowledge).

- When you get a particularly quiet group, it can be hard to decipher what students are thinking – are they tired, hungry, completely confused? If you are struggling to get participation, consider doing an occasional pulse check, asking students to go around the room and share a word that captures their current thinking or feeling. This can help you know what is happening and forces them to wake up, self-reflect, and engage.

- Call out and investigate troubling behaviour. If students seem particularly quiet, or particularly resistant, ask what is driving that behaviour. It can be a valuable long-term investment to dialogue about problematic classroom dynamics early in the term.

Establish Baseline Knowledge and Motivations

- If you want to be able to measure and assess student learning in your class, you may want to do some in-take assessments to measure students skill and knowledge before starting your course, which you can later compare with skill and knowledge development at the end of the semester. This can be done in group conversation, one-on-one conversations, or anonymous survey.

- Understanding students’ prior knowledge and their reasons for taking the course can help you revise your syllabus now that you know who is taking your class. For example, if you were expecting high prior knowledge, but your students generally have low prior knowledge, you may want to revise the syllabus. Additionally, framing readings and discussion topics around student motivations may prompt them to work harder and learn more.

Resources:

- Marilla Svinicki and Wilbert McKeachie, McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers

- University of Virginia, Center for Teaching Excellence, https://teaching.virginia.edu/collections/the-first-day-of-class

- Carnegie Mellon University, Center for Teaching Excellence and Education Innovation, http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/firstday.html

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Center for Faculty Excellence, https://cfe.unc.edu/teaching-and-learning/

- Washington University in St. Louis, The Teaching Center, https://teachingcenter.wustl.edu/

What is Reflection and Why it is Important?

How reflection enhances learning

There are a number of ways in which reflection enhances learning. These include:

- it deepens the understanding of the learner’s understanding of concepts or processes

- it provides opportunities for the learner to connect information and/or theory to their experience, other contexts, and/or connect it with what learnt before or in other classes

- it allows articulation of thoughts

- It allows learners to recognize the limitation of their work and be critical about it

- It provides meaning to an experience when the reflection is linked to a particular experience

- It promotes metacognition – thinking about thinking and strengthening learning skills

- It allows faculty to qualitatively assess the impact of an activity or experience

While there are many different ways in which reflection is defined in the literature, a comprehensive definition is the one of Rogers (2001) who consider reflection “as a cognitive and affective process or activity that (1) requires active engagement on the part of the individual; (2) is triggered by an unusual or perplexing situation or experience; (3) involves examining one’s responses, beliefs, and premises in light of the situation at hand; and (4) results in integration of the new understanding into one’s experience.”

A couple of useful academic literature and grey literature on reflections are below:

Academic literature on reflection – If you are interested in a summary of the academic debate on reflection, please read : Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in Higher Education: A Concept Analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37–57.

The following website organizes academic literature on the impact of reflection on learning outcomes classified by discipline.

Non-academic literature on reflection – If you want one website that provides a lot of information about reflection and its importance, go here .

A video on core components of reflection: this video is meant to be for students, and it is good to get quickly up to speed about the core components of reflection.

Useful Resources to Prepare Reflection Prompts and Reflection Activities

Starting point to prepare a reflective assignment: why do it and what to get out of it?

Like any other assignments, reflective assignments need to have a clear purpose that is communicated to the students. You could use this form to help structure your thinking.

While reflection is central to community-engaged and experiential learning activities, there are many reflective activities that can be done when learning does NOT have an experiential component outside the classroom. Indeed, reflection can be incorporated into anyone’s teaching practice.

What to take into account when planning a reflective assignment?

When thinking about reflective assignments, there are a number of things to consider:

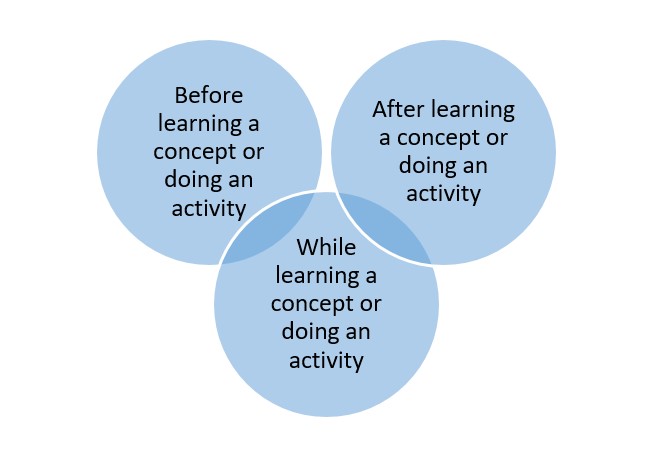

- WHEN should a reflective activity or assignment happen? – before, during, or after an activity/a class/an experience. See this document to look at what can be asked at different moments.

- What are the GOALS of reflection?

Two interesting classifications are the following:

-

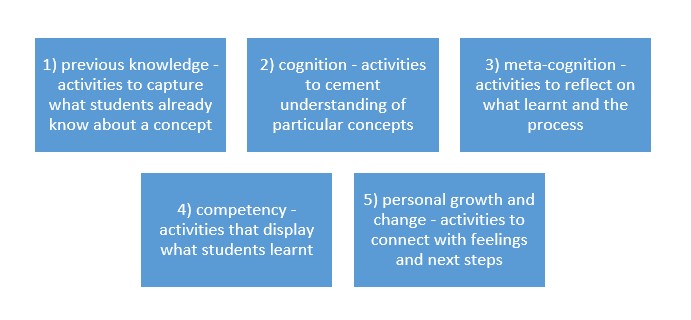

- The type of knowledge classification : 1) previous knowledge (used before students engage in an activity or topic), 2) cognition, 3) meta-cognition, 4) competency, and 5) personal growth and change.

-

- The 6 Rs of reflection – 1) reporting, 2) responding, 3) relating, 4) reasoning, 5) reconstructing and 6) repackaging (prompts and challenges summarized/adapted or taken from this article .

| Examples of prompt | Challenge for the writer | |

| 1) Reporting | What happened? What were the results? What is the new idea or concept? Explain important background information | Balancing details with accuracy and purpose. |

| 2) Responding | What emotional response does this elicit? What aspects of this experience, lesson, assignment, reading, issue, etc. were difficult or challenging, and why? Why did this matter to you? | Overcoming fear of revealing feelings; not slipping into clichés (safe ground) that don’t move thinking further |

| 3) Relating | How does this experience relate to another experience, lesson, assignment, reading, issue, etc.? Where do you see connections? What limits (differences, complications) are there in the connections you see? | Seeing beyond the most obvious connections; understand one side of the connection thoroughly so that the connection is not superficial or artificially imposed |

| 4) Reasoning | What limitations were there to this experience, lesson, assignment, reading, issue, etc.? What would [person/group] think of this? What are the underlying causes/parts? What are some alternative implications or meanings? | Shifting perspective without slipping back into defending the original point of view; challenging one’s own assumptions. |

| 5) Reconstructing | Given what you know now, if you were to approach this or a related experience, lesson, problem set, assignment, reading, issue, etc. again, how would you do it differently? How has it belief/understanding changed? How will this experience, lesson, assignment, reading, issue, etc. and your new knowledge, understanding of it change your future action or thought? | Making moves toward metacognition. |

| 6) Repackaging | What are the most important parts, and how do I put those into the genre I’m being asked to produce? What would a future employer or a graduate advisor need to know about this experience in order to understand me, my interests, and my ability to learn? When I reread the reflections for the whole term, what patterns do I see, and what can I do with them? | Condense experience in a way that does justice to what was learnt, and can be shared with an audience beyond the class. |

Specific activities organized by some of the R categories are here .

- What is the OUTPUT of these reflective activities?

For examples of mind-maps and photo captions reflective activities, look here . For examples of community murals, look here .Portfolios are other examples of more visual reflective activities, though they can also just be based on writing. Three useful links on portfolios include:

- For a visual option, see here .

- For a website/portfolio description, see here .

- For a portfolio mostly based on writing, see here .

- Whether you want the reflective activities to be INDIVIDUAL OR GROUP BASED. These reflective activities are mostly group based, and not always involving writing. While they are described in the context of community engaged learning projects, but can be used in other contexts

Reflection Rubrics

Reflection is generally accepted as a critical component of learning from experience but more limited research has been conducted to address the issue of how to assess reflection. There is definitely way to assess reflection but also agree that not all reflection needs to be assessed or graded. Some examples of rubrics are here , here , and here . This website provides useful suggestions for assignments/activities that are experiential in nature.

Rubrics for Journal Assessment

There are a number here , here , and here . See if you find them helpful.

How to Flip your Class

The ‘flipped classroom’ is probably a term you have encountered before. Although traditionally this is a style of teaching in which pre-recorded lectures and materials are uploaded before class, with the class time itself being used for discussions, you will find that many variations of this classic strategy have been created since. Below, you will find a comprehensive list of resources to help you learn how to flip your class. The online manuals will guide you in getting started, whilst the online tools and platforms provide valuable resources for making your flipped classrooms effective and interactive.

Online guides and manuals

Quick start guide: This quick, 1-minute (or less) start guide offers you an overview of the steps to ‘flipping’ a classroom in a lightning-fast glance.

Step-by-step video manual: This virtual manual on the website of the University of Texas at Austin is a gem. What you will love most about this are the accompanying videos that accompany each step, which not only explain, but offer recorded footage what each step is laying out, featuring actual instructors who have adopted the flipped classroom model in their courses.

Detailed ‘How-To’ manual : University of Queensland’s comprehensive manual, with links at crucial points to help you figure how exactly to make your flipped classroom happen.

Tips and advice

6 expert tips for flipping the classroom: Offers targeted advice and strategies to make the best of the flipped classroom experience.

5 best practices for the flipped classroom: This offers some strategies for conducting the ‘flip’. It also offers you thinking questions and/or reminders to have at the back of your head so that you stay true to the purpose of a flipped classroom and make full use of it.

9 video tips for a better flipped classroom: Similar to the link above, this online article gives you more tips on creating engaging content for flipped classrooms.

Free tools and platforms

7 free flipped classroom creation applications: Free applications for you to create audio and visual content for your flipped classrooms, some even allow interactions between users!

Below, you will find a few useful links for leading discussions, setting the space and climate, and communicating effectively.

Helpful guidelines for leading discussions

Facilitation Techniques : This downloadable PDF file offers some general guidelines and tips for leading discussions.

Effective classroom discussions : This document outlines what counts as a discussion, how to create expectations for student participation, clarify student/teacher roles and foster participation from students.

Setting the space and climate

Align seating arrangements with teaching objectives : Seating arrangements can have a tremendous impact on student participation. You will find that different arrangements have their respective benefits. This can help you plan your classes more effectively.

Communication

Characteristics of effective listening : This article compares the difference between an effective, interested listener and an uninterested, ineffective one.

Techniques for responding : Building off listening skills, this resource provides ways for professors to respond to student enquiries, giving helpful suggestions and framing strategies in point-form no longer than two lines.

Strategies for good conversation: 10 strategies for having good mentor-mentee conversations, useful for one-on-one meetings between professors and students, during office hours and even in class.

Last updated: 30 December 2020.

New research in educational literature has validated lecture-free and inquiry-based learning at all levels, particular in science courses. In addition, initiatives to combine “case studies” and content from multiple disciplines have helped increase the relevance and impact of science courses.

Eric Mazur, Harvard University Physics . Eric Mazur pioneered collaborative learning in large lectures, with peer instruction and with new technologies to dynamically assign partners to solve in-class physics problems. His work has been extensively validated and assessed. A wide range of resources can be found at his website.

Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative, University of British Columbia . Carl Wieman, a Nobel Laureate in Physics, has developed great resources for assessing and implementing new techniques in science teaching. He continues his work as a member of the Presidential Committee on Advanced Science and Technology (PCAST), and more recently as a newly appointed Director of a Science Education Initiative at Stanford University.

Physics Education Research at the University of Colorado . The UC Boulder group is very active in experimenting with new instructional technologies and new ways of teaching physics at all levels. One of their members, Noah Finkelstein, is also a member of the PCAST committee.

NASA Center for Astronomy Education – Astronomy 101 . This resource clearinghouse is home to a number of excellent lesson plans and educational papers that promote lecture-free learning, and in-class activities that are based on the latest research on exoplanets, dark matter, and other exciting topics.

Diane O’Dowd, HHMI Professor of Biology, UC Irvine . Diane O’Dowd has been developing lecture-free learning strategies for large classes at UC Irvine, as well as new techniques in mentoring research students, both undergraduate and graduate.

Harvey Mudd College Computer Science programme . At Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, the computer science class CS5/6 is required of all students, and is based on the Python language. Harvey Mudd College has been recognised as a leader in bringing women into computer science, and is now providing a biology-based course known as CS6 that blends computer science with problems in biology and environmental science. Find out more about on the HMC computer science course through the New York Times article.

Annie Murphy Paul on why College Lectures are Unfair . Annie Murphy Paul is a book author, magazine journalist, consultant and speaker who helps people understand how we learn and how we can do it better. Annie writes that a growing body of evidence suggests that the lecture is not generic or neutral, but a specific cultural form that favors some people while discriminating against others, including women, minorities and low-income and first-generation college students.

Ralph Bouquet Interviews David Waddington on Games and Teaching. David Waddington, a professor at Concordia University in Canada, investigated how Fate of The World (2011), a climate change simulation game, could impact people’s opinions about climate change. This articles argues that as games continue to become a more prominent part of K-12 classrooms, it’s imperative that we take advantage of their full potential to both augment content knowledge in science.

Last updated: 30 December 2020.

The following books are available at the Yale-NUS library for faculty who want to read more about how to enliven their classrooms and make their teaching effective.

| Author(s) | Title | Publisher | ISBN |

| Barkley, Elizabeth F.; Major, Claire Howell; Cross, K. Patricia | Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty | Jossey-Bass | 9781118761557 |

| Barbezat, Daniel P.; Bush, Mirabai | Contemplative Practices in Higher Education: Powerful Methods to Transform Teaching and Learning | Jossey-Bass | 9871118435274 |

| Nilson, Linda B. | Creating Self-regulated Learners: Strategies to Strengthen Students’ Self-Awareness and Learning Skills | Stylus Publishing | 9781579228675 |

| Stephen D. Brookfield, Stephen Preskill | Disscussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for Democratic Classrooms | Jossey-Bass | 9780787978082 |

| Mastascusa, Edward J.; Snyder, William J.; Hoyt, Brian S. | Effective Instruction for STEM Disciplines: From Learning Theory to College Teaching | Jossey-Bass | 9780470474457 |

| Bean, John C. | Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom | Jossey-Bass | 9780470532904 |

| Bean, John C. | Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom | Jossey-Bass | 9780470532904 |

| Kolb, David A. | Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development | Pearson | 9780133892406 |

| Davis, James R.; Arend, Bridget D. | Facilitating Seven Ways of Learning | Stylus Publishing | 9781579228415 |

| Layne, Prudence C.; Lake, Peter | Global Innovation of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Transgressing Boundaries (Professional Learning and Development in Schools and Higher Education) | Springer; 2015 edition | 9783319104812 |

| Ambrose, Susan A. | How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching | Jossey-Bass | 9780470484104 |

| Friend, Marilyn; Cook, Lynne | Interactions: Collaboration Skills for School Professionals | Pearson | 9780132774925 |

| Weimer, Maryellen | Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice | Jossey-Bass | 9781118119280 |

| Doyle, Terry | Learner-Centered Teaching: Putting the Research on Learning Into Practice | Stylus Publishing | 9781579227432 |

| Brown, Peter C.; McDaniel, Mark A. ; Roediger III, Henry L. | Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning | Harvard University Press | 9780674729018 |

| Light, Gregory; Micari, Marina | Making Scientists: Six Principles for Effective College Teaching | Harvard University Press | 9780674052925 |

| Lowman, Joseph; Lowman, Joseph | Mastering the Techniques of Teaching | Jossey-Bass | 9780787855687 |

| Svinicki, Marilla D.; Mckeachie, Wilbert J. | McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers, 14th Edition | Wadsworth Cengage Learning | 9781133940555 |

| Carnes, Mark C. | Minds on Fire: How Role-Immersion Games Transform College | Harvard University Press | 9780674735354 |

| Lang, James M. | On Course: A Week-by-Week Guide to Your First Semester of College Teaching | Harvard University Press | 9780674047419 |

| Barell, John | Problem-Based Learning: An Inquiry Approach | Corwin Press | 9781412950046 |

| Meyers, Chet; Jones, Thomas B. | Promoting Active Learning: Strategies for the College Classroom | Jossey-Bass | 9781555425241 |

| Conderman, Greg; Pedersen, Theresa | Purposeful Co-Teaching: Real Cases and Effective Strategies | Corwin Press | 9781412963393 |

| Handelsman, Jo; Pfund, Christine ; Miller, Sarah | Scientific Teaching | Freeman | 9781429201889 |

| Hamilton, Adam | Speaking Well: Essential Skills for Speakers, Leaders, and Preachers | Abingdon Press | 9781501809934 |

| Nilson, Linda B. | Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based resource for College Instructors | Jossey-Bass | 9780470401040 |

| Erickson, Bette LaSere; Strommer, Diane Weltner ; Peters, Calvin B. | Teaching First-year College Students: Revised and Expanded Edition of Teaching College Freshmen | Jossey-Bass | 9780787964399 |

| Brookfield, Stephen D. | Teaching for Critical Thinking: Tools and Techniques to Help Students Question their Assumptions | Wiley | 9780470889343 |

| Roberts, Helen; Gonzales, Juan C. | Teaching from A Multicultural Perspective | SAGE Publications | 9780803956148 |

| Burnham, Rika; Kai-kee, Elliott | Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience | Getty Publications | 9781606060582 |

| Gelman, Andrew; Nolan, Deborah | Teaching Statistics: A Bag of Tricks | Oxford University Press | 9780198572244 |

| Meyers, Chet | Teaching Students to Think Critically | Jossey-Bass | 1555420117 |

| Huston, Therese | Teaching What You Don’t Knoq | Harvard University Press | 9780674066175 |

| Bruff, Derek | Teaching with Classroom Response Systems: Creating Active Learning Environments | Jossey-Bass | 9780470288931 |

| Finkel, Donald L. | Teaching with Your Mouth Shut | Heinemann | 9780867094695 |

| Plank, Katthryn M. | Team Teaching: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy | Stylus Publishing | 9781579224547 |

| Sweet, Michael; Michaelsen, Larry K. | Team-Based Learning in the Social Sciences and Humanities: Group Work that Works to Generate Critical Thinking and Engagement | Stylus Publishing | 9781579226107 |

| Michaelsen, Larry K.; Fink, L. Dee ; Knight, Arletta Bauman | Team-Based Learning: A Transformative Use of Small Groups in College Teaching | Stylus Publishing | 9781579220860 |

| Gullette, Margaret Morganroth; Gullette, Margaret Morganroth | The Art and Craft of Teaching: Ideas, techniques, and practical advice for communicating your knowledge to your students and involving them in the learning process | Harvard University Press | 9780674046801 |

| Fraser, Kym | The Future of Learning and Teaching in Next Generation Learning Spaces (International Perspectives on Higher Education Research) | Emerald Group Publishing Limited | 9781783509867 |

| Kapp, Karl M. | The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education | Pfeiffer | 9781118096345 |

| Filene, Peter | The Joy of Teaching: A Practical lGuide for new College Instructors | The University of North Carolina Press | 9780807856031 |

| Booth, Alan; Hyland, Paul | The Practice of University History Teaching | Manchester University Press | 9780719054921 |

| Braxton, John M. | The Role of the Classroom in College Student Persistence: New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Number 115 | Jossey-Bass | 9780470422168 |

| Meyer, Jan H. F.; Baillie, Caroline ; Land, Ray | Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning (Educational Futures: Rethinking Theory and Practice) | Sense Publishers | 9789460912054 |

| Davis, Barbara Gross | Tools for Teaching, Second Edition | Jossey-Bass | 9780787965679 |

| Kaplan, Matthew; Meizlish, Danielle Lavaque-manty Deborah ; Sliver, Naomi | Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning | Stylus Publishing | 9781579228255 |