Embark on a voyage with experts to discover the galleon trade between Manila and Acapulco

Trade is undeniably a powerful force in history, and till today it continues to herald opportunities and change.

This was underscored in the webinar titled, “A Precursor to Globalisation: The Galleon Trade Between Manila and Acapulco (1564 to 1815)”, organised by Yale-NUS College to mark the 10th anniversary of the Pacific Alliance, a Latin American trade bloc. In collaboration with the Embassies of Mexico, Peru, and the Philippines, the panel discussion, held on 2 November 2021, transported attendees to a bustling trade route that existed four centuries ago, connecting Asia and America through the Pacific Ocean.

A screen capture of the panel engaged in discussion.

A screen capture of the panel engaged in discussion.

The panellists illuminated the significance of such transoceanic movement of goods, which had vast implications. An economic lens is often adopted when trying to understand the importance of trade but Dr Cuauhtémoc Villamar, an independent researcher on the Pacific history, noted that while there was substantial exchange of silver for high-end Asian goods along the “Manila Galleon…a system of trade under the rule of the Spanish monarchy”, it is equally important to consider other aspects, such as “demographic and biological changes”. After all, “steady interlinkages between communities across the Pacific led to substantive changes in food consumption, clothing, and diverse forms of material culture,” he expounded.

Science History Institute Doan Fellow Raquel A.G. Reyes shared further insights regarding the historical trade route by detailing a vivid picture of how Manila, which became one of the wealthiest entrepôts in Asia due to the galleon trade, was “a major force for cosmopolitanisation”. As “a hub for the storage, exchange and trans-shipment of goods”, Manila saw ships from Japan carrying silk, decorated screens, and lacquerware; Portuguese ships from Malacca, Bengal, and Cochin laden with spices, precious jewels, textiles, and tapestries and carpets; and boats from many other countries come through its port.

This exchange was not limited to goods, it extended to people as well: “by 1620, the city’s population stood at 41,400 of which 2,400 were Spaniards, 3,000 were Japanese, 20,000 were Filipinos, and 16,000 were Chinese”. Drawing from numerous examples ranging from the introduction of lady’s stockings to the consumption of tobacco and Hispanic food, Dr Reyes illustrated how imported goods affected everyday sensibilities involving “sartorial fashions, bodily scents, aesthetic and culinary tastes within Manila and beyond”.

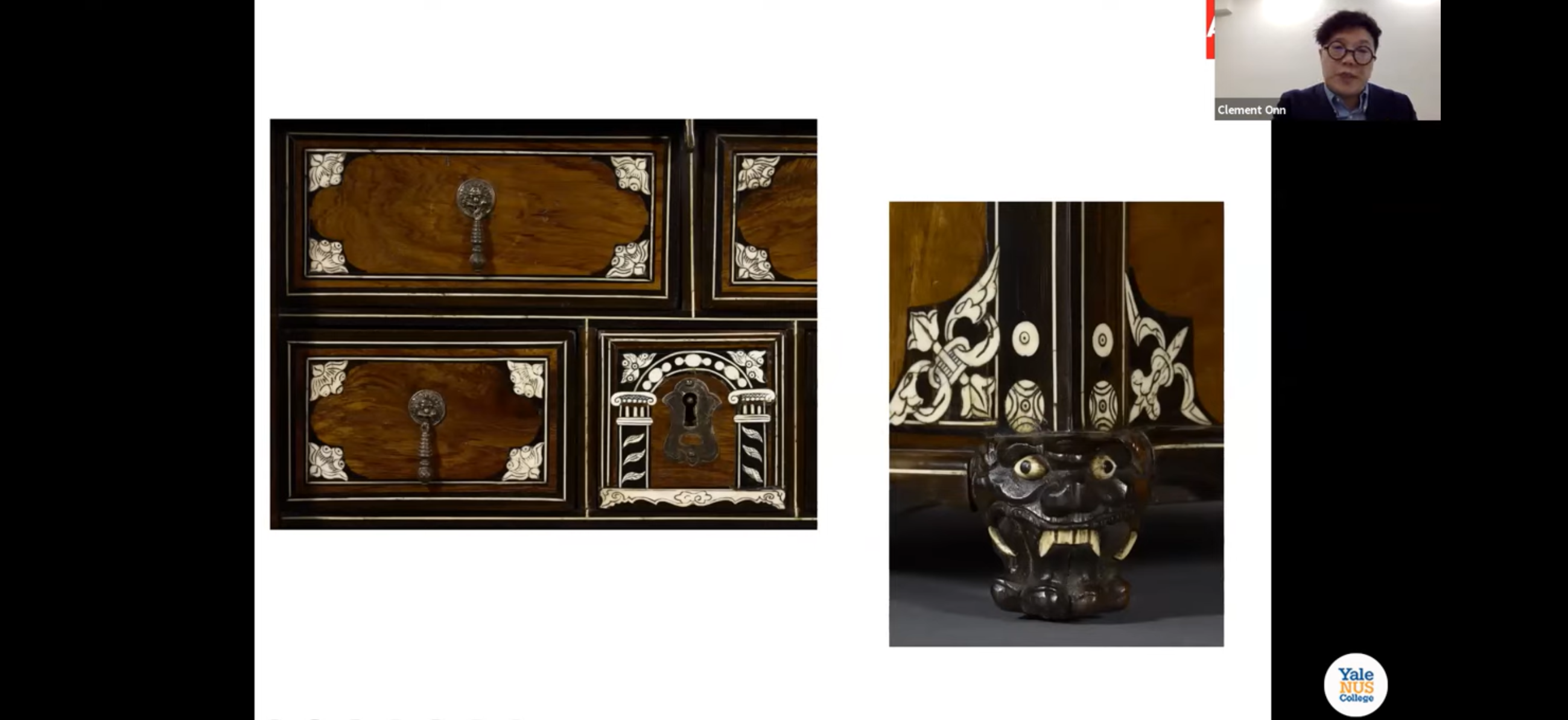

Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) Principal Curator (Asian Export Art & Peranakan) Clement Onn continued the topic of the benefits reaped from the transcultural nature of the galleon trade. He focused on a forefront portable cabinet made in the Philippines for export to European or the Americas markets, currently exhibited at ACM. The cabinet served as a clear example of the confluence of cross-cultural elements with its European style, Chinese designs, and the inclusion of an image depicting the foundation myth of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital city.

A screen capture of the forefront cabinet exhibited at Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore.

A screen capture of the forefront cabinet exhibited at Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore.

Project consultant and Ayala Museum Consulting Curator Florina H. Capistrano-Baker provided breadth to the discussion by shifting attention to the trade network between Manila and Salem. By comparing the differing Spanish and the American trading patterns of Manila hemp, sugar, indigo, and embroidered textiles and artwork, Dr Capistrano-Baker showcased “commercial rivalries that complicated Spanish enterprise in the Pacific, and…the intertwined lives of merchants and artists”.

When queried by Yale-NUS Assistant Professor of Humanities (History) Matthew Reader, who moderated the panel, if the term ‘globalisation’ can be used to describe the galleon trade, Dr Capistrano-Baker explained that while it depends on the definition of globalisation, it cannot be denied that “this was first time in the world where…Asia, Latin America, North America, and Europe connected; with ideas, objects, concepts and people moving all around the globe…impacting each other’s cultures. [Resulting] in the modern world having these hybridised cultures, showing the beginnings of the world as we know it today, where we are closely intertwined with each other”.

Dr Villamar also acknowledged that the historical trade route has far-reaching impact, which can be felt in present day. He crucially pointed out that lessons drawn from the Manila Galleon will prove useful in handling current issues—ongoing trade wars and the spread of diseases—and serve as a reminder to “interact more responsibly with [our] biological environment,” and to have “a clear and forcible regulatory framework of trade”.

This sentiment was echoed in the closing remarks given by the ambassadors of the United Mexican States, Peru, and the Philippines, respectively.

The Ambassador of the United Mexican States His Excellency Agustín García-López Loaeza mused that “[to] see your future, you have to see your past”. This rings true as the intention of remaining interconnected among the Latin American countries as well as with the Pacific is very much present in the Pacific Alliance (PA) and its decision to officially welcome Singapore as the PA’s first Associated State this year—building on the transformative forces of trade that have existed for centuries.

Click here to watch a recording of “A Precursor to Globalisation: The Galleon Trade Between Manila and Acapulco (1564 to 1815)”.