Yale-NUS students learn about religious rituals in Japan through a travel fellowship

Three students learnt more about Shinto and Buddhist practices to understand how religious rituals shape one’s value system

Yale-NUS students Loe, Edward Liau, and Christine Choo at Enyuuji Temple, which is located by a cliffside. All photos in the story were taken by Loe.

Yale-NUS students Loe, Edward Liau, and Christine Choo at Enyuuji Temple, which is located by a cliffside. All photos in the story were taken by Loe.

Through the Summer Travel Fellowship, a programme by the Yale-NUS Centre for International & Professional Experience, students get the opportunity to create their own learning journey via an intentional exploration of a new horizon or intellectual pursuit. Loe Luo writes about her Summer Travel Fellowship journey across Japan, which she embarked on alongside Edward Liau Yee Seng and Christine Choo Jia Ying (all from the Class of 2025).

Religion features significantly in Japanese culture. Many locals visit shrines and temples to pray on important occasions. Japan also holds religious festivals of various scales throughout the year to celebrate different historical occasions. With religious rituals playing a salient role in the lives of the locals, we were curious about what religion really means for the people in Japan. How do these rituals change how the locals think about other people and the world? How is “religion” understood in Japan?

Luckily, our questions did not remain unanswered. Through Yale-NUS College’s Summer Travel Fellowship programme, we embarked on a journey across Tokyo, Saitama, and Chichibu over the semester break. We observed rituals at temples and shrines, attempted pilgrimages, and attended religious festivals.

Jizo statues (on the left) can often be found along trails near temples as symbols of protection.

Jizo statues (on the left) can often be found along trails near temples as symbols of protection.

Our trip began rockily when we ended up on a perilous trekking path on our third day in Japan. We were trying to locate a section of the Enyuuji Temple that is known to be hanging by the cliffside. The temple is part of the 34 Kannon Temple Pilgrimage – a popular Buddhist pilgrimage in Chichibu dedicated to the bodhisattva of compassion, Kannon. Yet when our apprehension faded, we found ourselves grateful for the ordeal. The uphill climb brought us closer to fascinating bugs, elaborate spiderwebs, and tranquil silence. This defining moment has shown us how religious rituals such as a pilgrimage can create memorable encounters with the non-human world and bring about a novel intimacy with the little things we tend to overlook.

The festival parades often feature mikoshi (神輿; portable Shinto shrine) being carried around the town to bring blessings to the community.

The festival parades often feature mikoshi (神輿; portable Shinto shrine) being carried around the town to bring blessings to the community.

After leaving Chichibu, we arrived in Tokyo for two large-scale Shinto festivals. The Kanda Festival and Sanja Festival saw ceremonial parades, celebrations by district residents, and performances such as taiko (太鼓; Japanese drums) and mikomai (巫女舞; dances by shrine maidens).

The Sanja Festival drew large crowds of people both locally and internationally.

The Sanja Festival drew large crowds of people both locally and internationally.

Notably, the festivals were valuable bonding opportunities for locals living nearby. “I’m glad that the Kanda Festival finally revived after a four-year hiatus. I feel that the most significant aspect of the festival is its ability to bring people together as the residents had to communicate to plan for the events,” explained an elderly resident helping at one of the many community shop booths set up along a street in Chiyoda during the festival weekend.

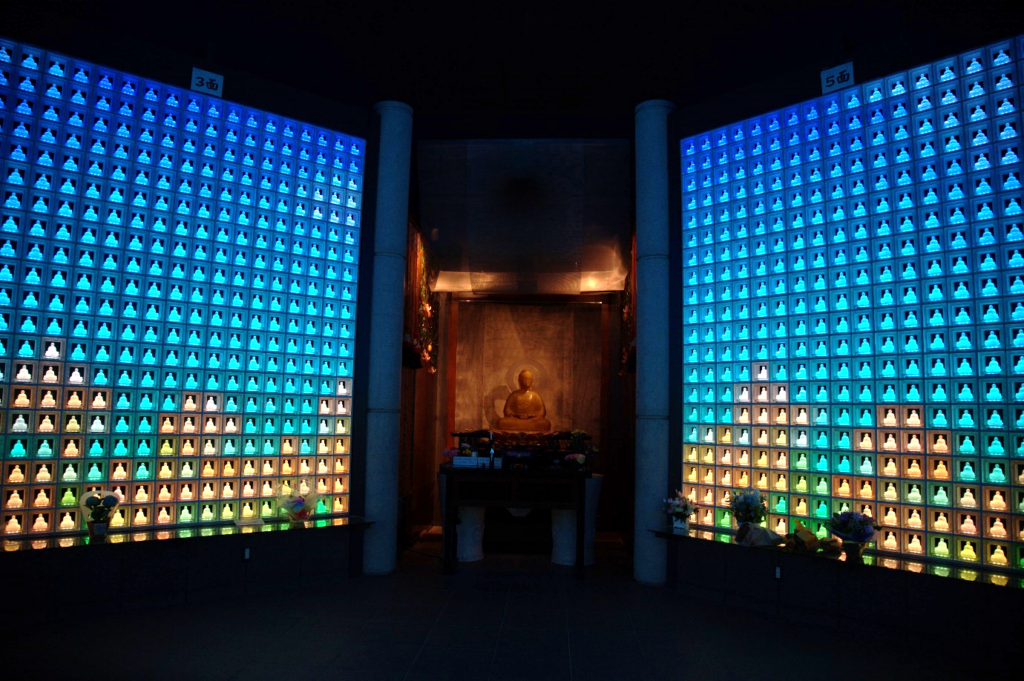

The temple houses over 2000 LED Buddha statues and visitors can enter the gated columbarium anytime with an issued electronic card.

The temple houses over 2000 LED Buddha statues and visitors can enter the gated columbarium anytime with an issued electronic card.

After the festivals, we went to many shrines and temples in Tokyo. One of the most memorable pitstops was our visit to the Koukokuji Temple – a columbarium with mini-Buddha statues that are lit by LED lights. The temple demonstrated how modern technologies can change traditional rituals, such as how we remember the dead, and got us wondering about the costs and benefits of these ways of memorialisation.

Interviewing the locals during our visits to the shrines and temples also yielded many other findings. One notable takeaway we had was realising how embedded religion is in everyday life in Japan. It is not unusual to hear residents say a quick prayer when passing by a temple on the way to work or drop by shrines to wish for good luck for their business or examinations. Several of our interviewees also said that these rituals have subconsciously shaped their behaviour, including being polite to other people, finishing all their food, and treating plants and animals with respect.

A pilgrim in Shikoku can be recognised by their iconic straw hat and white robe.

A pilgrim in Shikoku can be recognised by their iconic straw hat and white robe.

Our Travel Fellowship journey concluded with an attempt at a section of the Shikoku 88 Temple Pilgrimage. The arduous pilgrimage features 88 temple destinations that form a complete loop around Shikoku. Amidst our heavy breaths, we talked to many pilgrims to know more about what this spiritual journey meant for them. One of them shared that he wanted to search for post-retirement happiness via the pilgrimage after feeling great anguish when he was working. Another shared that she was walking to relieve the guilt she felt toward her late husband.

As we came to the realisation that our journey was about to end while walking about the premises of Okubo Temple, the 88th temple of the pilgrimage, our group fell into a reflective mood. The trip certainly gifted us with knowledge about what different religious rituals mean to the people in Japan. Though more poignantly, we were also glad to be bringing back precious memories of the interactions we have had with the people we met along the way.